Analysis of Case Study Results

INTRODUCTION

An analysis of results for the six case study locations reveals various trends and themes regarding the efficacy of wild-domestic sheep separation policy. Biophysical geography and land ownership, bighorn population histories prior to outbreaks, nearby domestic sheep, epizootic events, and policy documents shed some light on what location/policy combinations were more or less effective at preventing wild-domestic sheep interaction leading to disease. However, examining the nine policy analysis criteria for each location revealed the most specific insights into policy efficacy.

BIOPHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND LAND OWNERSHIP

Of the cases examined, aside from sometimes increasing the difficulty of locating and monitoring domestic sheep and wandering bighorns, biophysical geography did not seem to play a significant role in determining policy efficacy. However, choosing case study locations to be representative was generally successful in representing landscapes pertinent to bighorn-domestic sheep interaction. Some representativeness regarding particular landscapes’ policies was also somewhat achieved or at least potentially achieved, but to fully confirm such representation, many more case study analyses would need to be undertaken. Locations vary and are representative of much of the physical geography of bighorn habitats in the U.S., which feature their own forms of interaction policy.

The Tobin Range and Hays Canyon Range are arid, north-south high desert mountains with sagebrush and juniper. They are representative of California bighorn habitat and the more northerly desert bighorn ranges (BLM 2012; NDOW 2012a, c; Google Earth 2012; BLM 2007a; Toweill and Geist 1999). They are also somewhat representative of Nevada’s wild-domestic sheep interaction policies and how they are implemented or neglected in such areas. Bighorn die-offs in areas with domestic sheep have continued in Nevada when managers probably should have known better. This is evidenced by winter 2009-2010 die-offs in the Ruby Mountains and East Humboldt Range (WAFWA 2010c) and a summer 2011 die-off in the Summer Mountains (DeLong 2011).

Collectively, the Highland/Pioneer Mountains and Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains are representative of many bighorn ranges in the Rockies with grassy slopes, fir and pine forests, alpine tundra, and high peaks reaching from up to 3,048 m (10,000 ft) to over 3,658 m (12,000 ft) (George et al. 1996; MFWP 2010; Reese 1985). The Highland/Pioneer and Tarryall/Kenosha locations may also be representative of what interaction policy is like in areas where bighorns are native or were established prior to the domestic sheep disease threat becoming prominent.

The Bonner/West Riverside habitat (with meadows, talus slopes, and forested foothills) is representative of more populated, lower elevation portions of the interior Rockies where bighorns live near subdivisions in narrow river valleys or canyons (MFWP 2010; Google Earth 2012). The author has visited similar bighorn habitat in Colorado’s Big Thompson Canyon. As predicted, the presence of Bonner/West Riverside bighorns near people provided a unique opportunity to study the disease issue in the context of a populated area. Things like subdivision covenants and city weed control via domestic grazing were important factors there but not in the other studied locations (MFWP 2010). Bonner/West Riverside may be representative of other regions hosting bighorns near residential development.

Aldrich Mountain is representative of transitional habitat with varied terrain, elevations up to 2,118 m (6,950 ft), grassy slopes, and ponderosa pine (USFS 2010a). It is also in a region where high desert meets mid-latitude mountain forest (Google Earth 2012). It is uncertain just how representative Aldrich Mountain’s policies may be of similar regions, partly because not many policy details were discovered for Aldrich Mountain.

High, steep river canyons were a bighorn habitat region not represented in this study. Because of Hells Canyon, this type of habitat hosted significant levels of bighorn disease deaths from 1990-2010 (Arthur et al. 1999; Cassirer et al. 1996). The extremely hot and cacti-clad southerly and Sonoran Desert ranges of desert bighorns were also not represented in this study. However, compared to other regions in the U.S., they did not experience significant disease outbreaks from 1990-2010 (Arthur et al. 1999; Jansen et al. 2007).

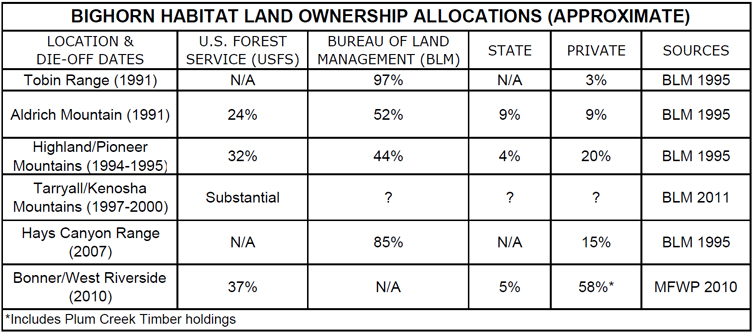

Habitat ownership/management designations varied for each location. Before this study was carried out, assumptions were made regarding types and quantities of land ownership, which played a role in influencing some areas’ policy efficacy. Going into this study, original suppositions were that desert and California bighorns would mainly be on BLM land. That proved correct. California and desert bighorns from case study locations lived in habitat that was more than 50 percent BLM land. However, Aldrich Mountain California bighorns lived on land with notably mixed ownership (BLM 1995).

Another supposition was that Rocky Mountain bighorns would mostly be on USFS land. This assumption was not wholly accurate. Land ownership for Rocky Mountain bighorns was more mixed than for the locations of the other subspecies. Highland/Pioneer bighorn habitat was mostly BLM land, Tarryall/Kenosha range was primarily USFS land, and Bonner/West Riverside bighorn use areas were mainly private land (BLM 1995; MFWP 2010; BLM 2011). The varied mosaics of land ownership probably made managing the disease issue more difficult and may have contributed to outbreaks and policy inefficacy.

All bighorn populations lived in habitat that included private lands. This was expected, but the amounts of private land were surprisingly significant. For example, including timber company land, the Lower Blackfoot Hunting District (containing the Bonner/West Riverside bighorns) was about 58 percent private land in 2010 (MFWP 2010). Compared to the situation with grazing allotments on public land, wildlife and land management agencies have far less control over domestic sheep on private land, which increases the difficulty of forming and effectively implementing interaction policy. Private land domestic sheep proved to be a troublesome issue in the Tobin Range, Highland/Pioneer Mountains, Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains, and Bonner/West Riverside (Ward et al. 1997; Tanner 2012a; Aune et al.1998; MFWP 2010; Edwards et al. 2010).

BIGHORN POPULATION HISTORIES PRIOR TO OUTBREAKS

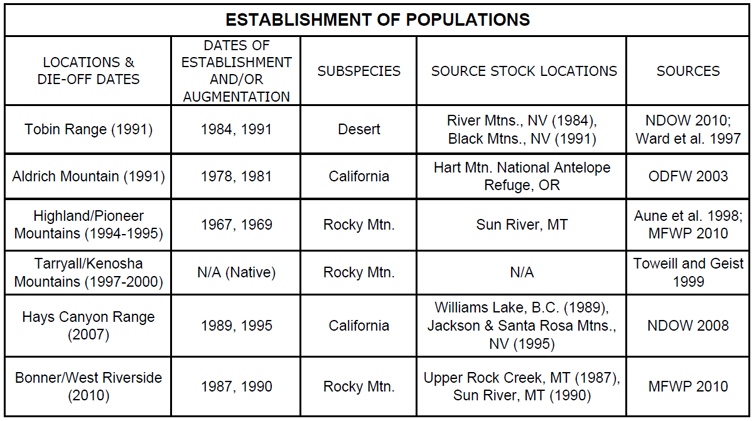

Five of the six case study bighorn populations were transplant populations established by wildlife management agencies in areas where bighorns died off in the historic past. Population establishment dates range from 1967-1989. All transplant populations were augmented once after initial seed herd translocation. Examining bighorn population histories reveals some insights on disease patterns and policy trends.

In the case of the Tobin Range, an augmentation of 18 bighorns was added to the existing population during the same year a disease outbreak struck (Ward et al. 1997). Ward et al. imply that such augmentations may contribute to disease outbreaks because augmentation bighorns may harbor disease antibodies that are infective to their new wild sheep companions (1997). However, the Tobin bighorns began to decline in August 1991 when domestic sheep were noticed trespassing on their habitat (Cummings and Stevenson 1995). The Tobin population was not augmented until October 1991 (Ward et al. 1997). That fact seems to rule out the possibility of augmentation bighorns being a primary disease catalyst in the Tobin Range, which implies an author or authors in Ward et al. 1997 may have been advocating policies that did not emphasize domestic sheep restrictions.

The Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains were the only case study location containing a native bighorn population (Toweill and Geist 1999). Compared to the other locations, the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains had a notable lack of interaction policy (George 2012). Their bighorns’ native status may have contributed to the lack of policy. For other locations, when new bighorn populations were established, the presence of domestics was considered beforehand, and correlating policy (some of it logical and at least somewhat effective) was formulated prior to reintroductions (BLM 1982; Foster 2012; Flores, Jr. 2012; MFWP 1986).

The Aldrich Mountain, Hays Canyon Range, and Highland/Pioneer bighorn populations demonstrated increasing trends not long before being hit by disease (USFS 1990a; ODFW 2003; NDOW 2006; MFWP 2010). These population increases likely reduced efficacy of interaction policy and made separation more difficult. Larger numbers of bighorns may have also contributed to more rapid spread of disease. According to Aune et al., the increase of the Highland/Pioneer bighorn population could help explain why it suddenly suffered a pneumonia die-off in 1994 after coexisting with domestic sheep for about 20 years with no apparent disease problems (1998). The importance of wild-domestic interaction policy may be less obvious to and more neglected by wildlife and land managers when bighorn populations are smaller.

NEARBY DOMESTIC SHEEP

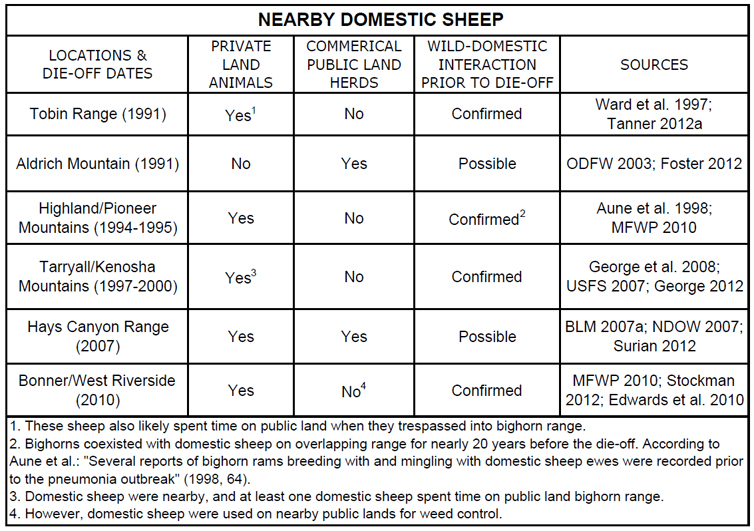

The presence of nearby domestic sheep necessitates wild-domestic sheep interaction policies in the first place. If nearby domestic sheep are on private land, they can be more difficult to control, which can reduce policy efficacy. Additionally, the case of Aldrich Mountain illustrates some interesting temporal factors regarding transmission and the amount of time sheep are on the range. Furthermore, where the domestic sheep industry has strong political power, the effectiveness of interaction policies is diminished.

Going into this study, a major assumption was that most case study locations were in areas where domestic sheep grazed on public land as part of commercial operations. This assumption drove analysis criteria formulation. It explains why so many criteria relate to grazing allotments. However, the assumption proved incorrect. Five of the six case study locations were in areas that featured bighorn habitat near private land domestic sheep. In three locations, domestic sheep on private land were the only known domestic sheep in the area. Around the time of each outbreak, domestic sheep were on public land allotments in only two locations.

The presence of domestic animals on private lands can limit and preclude wildlife management agencies’ abilities and authority to mange livestock in efforts to protect wildlife. The private land factor likely contributed to disease outbreaks. Policy may be more effective or at least easier to implement when all domestic animals are on public lands. For example, a domestic sheep grazing allotment near Aldrich Mountain was altered after that area’s epizootic, and no further disease outbreaks occurred there (ODFW 2003). Private land domestic sheep are a prime example of a factor contributing to wildlife federalism complications. According to Anderson and Hill: “The history of wildlife management shows that a balance can be struck between individual, state, and national control, but this balance is currently missing” (1996).

The Aldrich Mountain situation is unique among the case studies because, based on findings for this project, the last time that confirmed and authorized domestic sheep grazing occurred on public land in the area was two years before the time of the die-off (Gibson 2012). That indicates timing factors may have been influential. Initial infection and transmission to larger groups of wild sheep may have happened early with isolated bighorns that interacted with domestic sheep or used habitats on which they had been present before returning to their herds in 1991. Or, perhaps stray domestic sheep from 1989 remained on Aldrich Mountain by 1991. With allotment users requesting permission to graze 600 domestic sheep in 1989 (USFS 1989), stray animals seem likely. Grazing permittees may have also grazed domestic sheep without permission during 1991. Nonetheless, this is speculation. Aldrich bighorns may have contracted pneumonia from a non-domestic sheep source. Rules addressing cleanup of the range after domestic sheep are supposed to be off it could improve effectiveness of bighorn-domestic sheep interaction policies.

Nearby domestic sheep can be a greater obstacle to effective interaction policy in areas where the domestic sheep industry has significant political influence. Both Nevada and Montana stand out for these reasons (WAFWA 2010c; Person 2009; MFWP 2010). As mentioned in Chapter II’s controversy section, as recently as 2010, “[NDOW] caught hell from one of their new Commissioners” for killing a bighorn that came into contact with domestic sheep (WAFWA 2010c, 2). Reactions like this increase the difficulty of effectively implementing fatal bighorn removal policy. The MFWP makes special efforts to address the domestic sheep industry’s preferences in its bighorn management plan (2010), which reflects the strength of that industry in the state. The views and influence of domestic sheep producers (largely in the form of stubbornness and lack of cooperation) reduced the efficacy of interaction policies in Nevada’s Tobin Range and Hays Canyon Range and in Montana’s Highland/Pioneer Mountains (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991; Flores, Jr. 2012; Frisina 2012).

OUTBREAK SUMMARIES

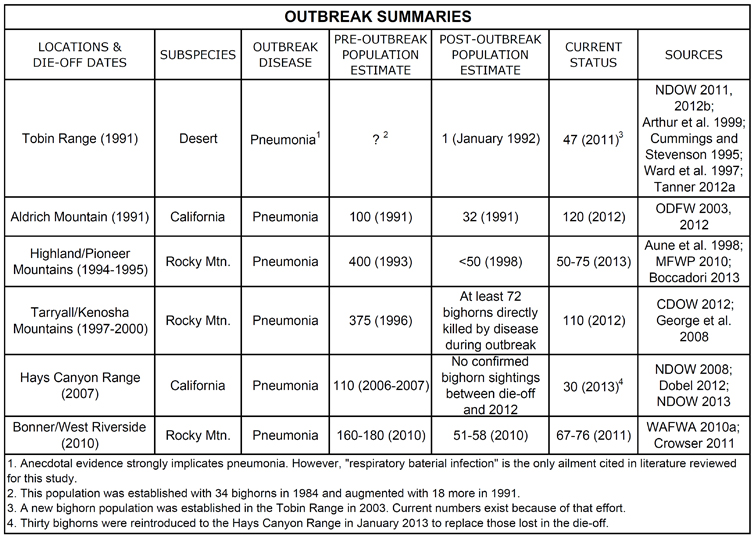

Each case study location experienced an outbreak that either eliminated or greatly reduced its bighorn population. Variable recovery levels for the bighorn populations shed light on policy efficacy and disease trends.

The Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains population was native, and it had already experienced disease die-offs in the 1800s and 1950s (CDOW 2009). This could explain why, despite suffering suppressed lamb recruitment after their 1997-2000 pneumonia outbreak (George et al. 2008), the population managed to survive in higher numbers than other disease-stricken populations. The author speculates that perhaps some Tarryall/Kenosha bighorns have at least partial immunity to certain varieties of pneumonia bacteria because of their ancestors’ exposure. Nonetheless, because of the population’s strong historic association with disease, one would think wildlife managers might have taken better precautions with modern-day policies. The historic die-offs did not appear to have influenced Tarryall/Kenosha interaction policies by the 1990s.

Some case study populations were hit harder by disease than others. For example, Aldrich Mountain bighorns largely recovered from their die-off (ODFW 2012). The post-outbreak alteration of domestic sheep grazing practices (ODFW 2003) may have contributed to their recovery. In contrast, disease completely wiped out Tobin Range bighorns in the early 1990s (Cummings and Stevenson 1995). There have also been no confirmed bighorn sightings in the Hays Canyon Range after that region experienced a 2007 die-off (Dobel 2012). In discussions with biologists regarding the Hays Canyon Range, nothing was said about the area’s domestic sheep allotments having been modified since the die-off. Lack of allotment modification policies after a die-off can reduce the chances for straggler bighorns to survive or for new populations to become established.

Highland/Pioneer bighorns were severely reduced by disease, and lamb recruitment has remained suppressed (Aune et al. 1998; MFWP 2010). The author speculates that this slow road to recovery may relate to continued contact with domestic sheep. However, suppressed lamb recruitment can occur after only a single epizootic (USFS 2006). As of 2010, domestic sheep hobby farms were still an issue in Highland/Pioneer bighorn range (MFWP 2010). Additionally, according to meeting minutes of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ (WAFWA) Wild Sheep Working Group (WSWG), as of May 2009, the BLM Field Office in Butte, Montana (near Highland/Pioneer bighorns) had “completely ignored [WAFWA’s important wild-domestic sheep separation recommendations], and continued to permit/advocate/allow conflicting activities in close proximity to occupied [bighorn] habitats” (WAFWA 2009, 3). While this could indicate genuine neglect by the BLM and/or its prioritization of domestic sheep over the survival of bighorns, one must also remember that domestic sheep in the Highland/Pioneer Mountains area occur on private land where public agencies have limited control over livestock. According to MFWP, public land domestic sheep grazing allotments do not exist in the area (2010).

Bonner/West Riverside bighorns suffered heavy losses, but the population has somewhat increased compared to initial post-outbreak numbers (WAFWA 2010b; Crowser 2011). This relates to the fact that the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP) lethally culled numerous bighorns during the outbreak to prevent spreading of disease (Crowser 2011). In emergency situations, heavy culling may be an effective way to prevent further wild-domestic sheep interaction and disease spread.

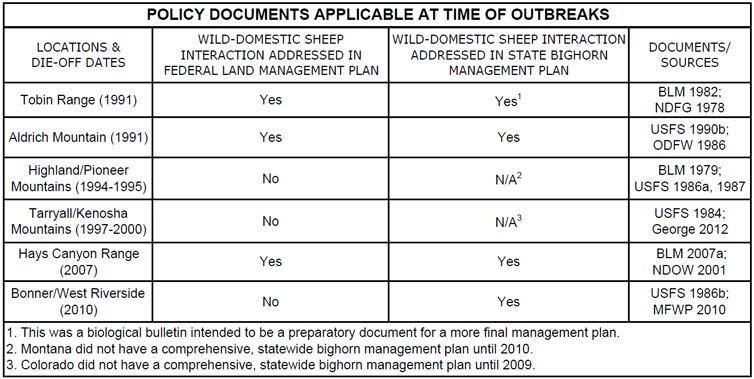

POLICY DOCUMENTS

Location-specific federal land management plans for only three case study areas addressed the wild-domestic sheep interaction issue. The oldest federal plan addressing the disease problem was from 1982 (BLM 1982), and the most recent was from 2007 (BLM 2007a). Both of the investigated comprehensive state bighorn management plans containing policies that were applicable at the time of examined outbreaks heavily addressed the disease issue and contained reasonable and logical science-based policies (NDOW 2001; MFWP 2010). However, these policies were not always effectively implemented or enforced prior to their correlating case study die-offs (Flores, Jr. 2012). What was sort of a proto-management plan (Nevada’s 1978 desert bighorn biological bulletin) made a clear recommendation against wild-domestic sheep coexistence, but also reflected some outdated and erroneous knowledge regarding the disease threat of domestic sheep (NDFG 1978). For policy documents to be effective at wild-domestic sheep separation, they should actually be enforceable. To make bighorn protection components of documents more effective, more binding language should be inserted. For example, instead of mere guidelines, USFS plans should have more enforceable standards that are binding and address protecting bighorns from domestic sheep.

POLICY ANALYSIS CRITERIA

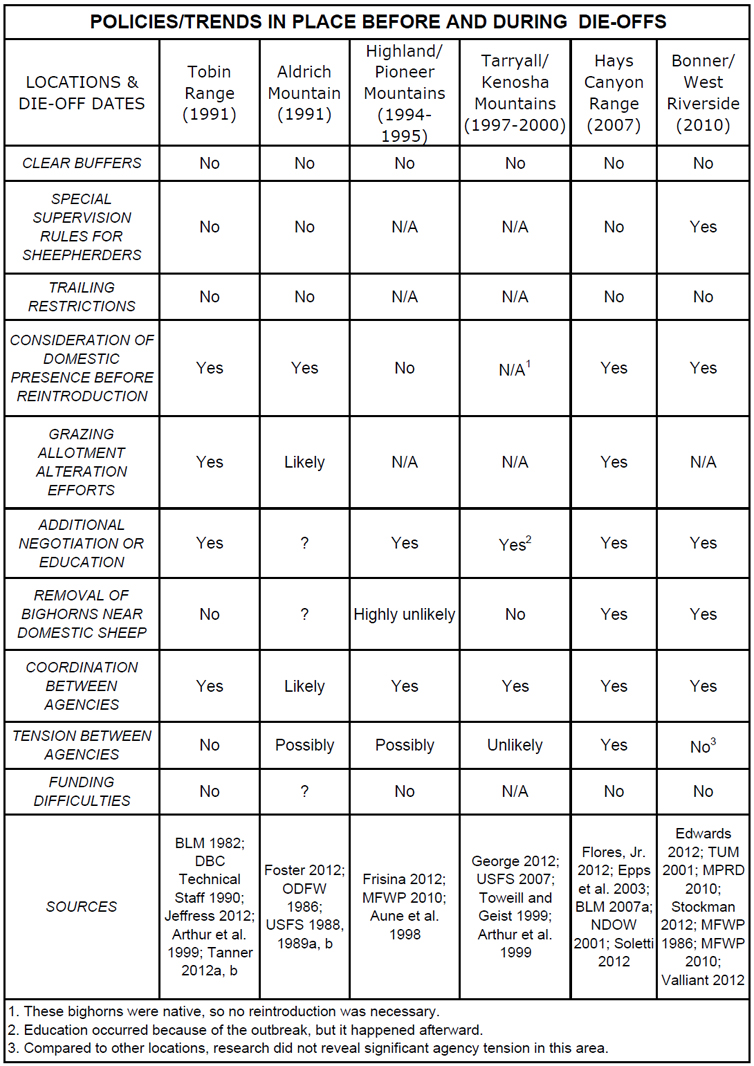

1. Clear Buffers

None of the examined case study locations had clearly defined buffer zones for separating wild and domestic sheep. Buffer zones were featured in the Desert Bighorn Council’s (DBC) 1990 guidelines (DBC 1990) and the BLM’s 1992 (BLM 1995) and 1998 (BLM 1999) recommendations for managing domestic sheep in bighorn habitat.

The 1990 DBC guidelines were applicable to the Tobin Range, and the 1998 BLM recommendations were applicable to the Hays Canyon Range. Montana’s bighorn management plan (MFWP 2010) also specifically mentions buffer guidelines, and it was applicable to Bonner/West Riverside.

As Schommer emphasized, buffers are not always effective because of the sometimes unpredictable and wide-ranging movement patterns of wild and domestic sheep and the rugged terrain both species often inhabit (USFS 2010b). Also, though biologists have since learned that buffer zones of about 13.5 km (roughly 9 mi) wide are inadequate, that has not stopped the BLM from using the 13.5 km figure in its resource management planning processes (Tanner 2012a; BLM 1999). The ODFW, MFWP, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have also used the 9-mile buffer value (Foster 2012; MFWP 2010; USFWS 2000). Regardless of their inefficacy, the lack of attempts at establishing buffers may have been a key policy weakness that contributed to disease striking all case study locations.

2. Special Supervision Rules for Sheepherders

Five of six examined locations lacked special supervision rules for sheepherders. This lack of supervision rules indicates weak policy that may have contributed to wild-domestic sheep disease transmission. Bonner/West Riverside was the only case study area that had location-specific supervision rules for sheepherders. These supervision rules applied to the City of Missoula grazing domestic sheep on open space lands to control invasive plants (TUM 2001). Missoula does not graze domestic sheep in January, which was when the Bonner die-off occurred (Stockman 2012; WAFWA 2010b). Thus, the weed control supervision rules in the Bonner/West Riverside region appear to be an example of effective interaction policy that successfully separates wild and domestic sheep.

3. Trailing Restrictions

None of the examined case study locations had trailing restrictions on domestic sheep. This lack of trailing restrictions indicates policy inefficacy that may have contributed to disease outbreaks. However, trailing restrictions existed in print as broad guidelines (DBC Technical Staff 1990; BLM 1999) that could have been applied to the Tobin Range and Hays Canyon Range. In the case of the Hays Canyon Range, the BLM had reasonable, logical policy (BLM 1999, 2007a, b) that they neglected to implement or enforce (Flores, Jr. 2012).

4. Consideration of Domestic Presence Before Reintroduction

The concept of prohibiting bighorn reintroduction to a site if it currently hosted domestic sheep was considered or part of policy in all but one case study location that hosted transplanted populations. This consideration may have delayed disease outbreaks and can demonstrate effective interaction policy. However, to prevent disease outbreaks, existing domestic sheep presence should be considered and resolved more thoroughly and effectively than what transpired in this project’s case study locations.

5. Grazing Allotment Alteration Efforts

Grazing allotment alteration efforts were successfully implemented in at least two locations before die-offs: the Tobin Range and the Hays Canyon Range (Tanner 2012a; Flores, Jr. 2012; BLM 2007a). Allotment alteration may have delayed the onset of disease from domestic sheep. However, in the Hays Canyon Range, a domestic sheep allotment was preserved near bighorns (BLM 2007a). If grazing allotment alteration will contribute to effective policy, it should be done thoroughly and consistently throughout a bighorn population’s range.

6. Additional Negotiation or Education

General negotiation and education aside from that related to altering grazing allotments happened in at least five of the six case study locations. Education and negotiation can be ineffective if done too late, as was the case in the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains where agency representatives talked to a domestic sheep owner after the region’s bighorn disease outbreak (George 2012). They can also be ineffective if locals are recalcitrant or skeptical of science. However, education and negotiation can lead to effective policy when multiple parties recognize the same risks and coordinate. This was the case in the Bonner/West Riverside area regarding the City of Missoula’s grazing of domestic sheep. Effective negotiation and education involves all parties getting on the same page and participants’ acceptance of wild-domestic sheep disease science.

7. Removal of Bighorns Near Domestic Sheep

Cases of wildlife managers removing bighorns that got too close to domestic sheep were discovered for two case study locations: the Hays Canyon Range and Bonner/West Riverside (Epps et al. 2003; MFWP 2010). A bighorn interacting with domestic sheep on a mountain range adjacent to the Hays Canyon Range was removed seven years before the area’s 2007 die-off (Western Hunter 2000). This indicates the removal may have delayed a disease outbreak and served as an example of effective separation policy implementation.

In the Bonner/West Riverside area, two bighorns near domestic sheep were removed 10 years before that region’s 2010 disease outbreak, which also implies effective policy delaying disease. However, the removed bighorns were near domestic sheep grazed by the City of Missoula, which has a history of cooperation with MFWP (MFWP 2010). The 2010 Bonner/West Riverside die-off likely resulted from subdivision animals. Thus, the bighorn removal policy is most effective if done consistently for all at-risk wandering wild sheep.

Nonetheless, Curtis M. Mack (Bighorn Sheep Recovery Project Leader for the Nez Perce tribe) criticizes the efficacy of the removal policy and indicates that sometimes “the need to remove bighorn sheep because of interactions with domestic sheep or goats should be viewed as a management failure triggering implementation of more effective separation strategies to prevent contact and preclude the need for further removal of wild sheep” (2008, 215).

8. Coordination/Tension Between Agencies

Bighorn-domestic sheep disease-related coordination between different levels of government agencies existed for at least five of the case study locations. Coordination can help delay or prevent disease. However, coordination by itself is not necessarily an effective policy quality, considering five examined locations’ agencies coordinated and failed to prevent bighorn die-offs. To be an effective component of policy, coordination must be consistently implemented with parties who care about taking action in a timely manner.

Tension between different agencies regarding the disease issue was indicated for two locations (Aldrich Mountain and Highland/Pioneer Mountains), unlikely in one location (Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains), not detected for one location (Bonner/West Riverside), and definite for at least one location (Hays Canyon Range). Tension and disagreement can reduce policy efficacy by delaying or preventing policy formulation or implementation. In all locations where tension seemed to play a role in wild-domestic sheep interaction management, it appeared to make implementation of policy less effective.

9. Funding Difficulties

Regarding wild-domestic sheep interaction practices, funding difficulties were not discovered to be in existence or significant for any of the case study locations. This project’s results reveal that funding difficulties probably did not contribute to the case study disease outbreaks. While funding in the case study locations might have contributed to more personnel addressing wild-domestic sheep interaction, field enforcement of regulations, separation barriers, expanded education, and special monitoring programs, special funding for these things appeared to not be a concern of wildlife managers around the time of each outbreak. In improving policy efficacy, factors like coordination, will to actually implement enforcement, and education are probably more important than funding. When it comes to protecting bighorns from domestic sheep, biologist Mike Dobel emphasized that politics can be more influential than money (2012).

GENERAL TEMPORAL TRENDS

One temporal trend revealed by this study involves key wild-domestic sheep interaction policies being released very close to the time of a region’s die-off. For example, the Tobin Range’s 1991 desert bighorn die-off happened a year after the DBC released special guidelines (DBC 1990) for managing domestic sheep in desert bighorn habitat. Additionally, important wild-domestic sheep policy was described in a Malheur National Forest plan (USFS 1990b) released a year before the Aldrich Mountain die-off. This is an interesting coincidence, but it is worth noting that the domestic sheep implicated in that outbreak were actually on the nearby Ochoco National Forest. Furthermore, Montana’s first comprehensive bighorn management plan (MFWP 2010) was released in January 2010, which was also when the Bonner/West Riverside outbreak happened. Having die-offs happen in such close temporal proximity to policy publication indicates a lag time between policy publication and implementation. It also underscores the urgency and necessity of better bighorn-domestic sheep separation policies. Such policies do not address vague, distant threats. They deal with a current problem that regularly occurs and must be confronted.

Based on the research performed for this project, the wild-domestic sheep disease issue gained prominence from 1990-2010 in policy documents, politics, and in the minds of agency biologists. For example, policy information preceding the 1991 Tobin Range and Aldrich Mountain die-offs was more difficult to find than for all other die-offs. However, policy information applicable to the 2010 die-off was the most abundant and easiest to discover. As time passed, more wild-domestic sheep interaction policies were formulated and documented. For instance, within the time range of 1990-2010, Nevada and Montana significantly strengthened and expanded their wild-domestic sheep interaction policies and covered them in their management plans (NDOW 2001; MFWP 2010). The other case study states also now have reasonable management plans with logical disease policy in print (ODFW 2003; CDOW 2009).

While improved policies may not always be more effective on the ground, policy improvement on paper has occurred. History indicates that policies will keep improving, despite obstacles. Nonetheless, considering how frequently bighorn die-offs continue to occur, the improvement of policy implementation is crucial but more uncertain.REFERENCES

Anderson, Terry L., and Peter J. Hill. 1996. Wildlife. In Environmental federalism: Thinking smaller, ed. Jane S. Shaw. Property and Environmental Research Center. http://perc.org/ articles/environmental-federalism-2 (accessed May 12, 2013).

Arthur, Steven M., Ian Hatter, Alasdair Veitch, John Nagy, Jean Carey, Jon T. Jorgenson, Raymond Lee, John Ellenberger, John Beecham, John J. McCarthy, Gary Schlichtemeier, Larry T. Gilbertson, Bill Dunn, Don Whittaker, Ted A. Benzon, Jim Karpowitz, George Tsukamato, Kevin Hurley, Steven G. Torres, Craig Mortimore, Mike Oehler, Patrick Cummings, Craig Stevenson, Eric Rominger, and Doug Humphreys. 1999. Appendix A: Wild sheep status questionnaires. In proceedings of 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference, Reno, NV. April 6-9.

Aune, Keith, Neil Anderson, David Worley, Larry Stackhouse, James Henderson, and Jen’E Daniel. 1998. A comparison of population and health histories among seven Montana bighorn sheep populations. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 11th Biennial Symposium, Whitefish, MT. April 16-20.

Boccadori, Vanna. 2013. Wildlife Biologist (Butte Area), Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. February 23.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1979. Management Framework Plan: Dillon Summary, Montana. Butte, MT. [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1982. Sonoma-Gerlach Management Framework Plan. Reno, NV. http://www. blm.gov/nv/st/en/fo/wfo/blm_information/rmp/documents.html (accessed May 29, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1995. Mountain Sheep Ecosystem Management Strategy in the 11 Western States and Alaska. N.p. ftp://ftp.blm.gov/pub/blmlibrary/BLM publications/StrategicPlans/Wildlife/ MountainSheepEcosystem.pdf (accessed May 11, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1999. Attachment 7: 1998 Revised Guidelines for Domestic Sheep and Goat Management in Native Wild Sheep Habitats. In Challis Resource Management Area: Record of Decision and Resource Management Plan. Salmon, ID. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/id/plans/challis_rmp.Par.8185.File.dat/ entiredoc_508.pdf (accessed May 12, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2007a. Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement: Surprise Field Office, Volumes I and II – May 2007. Cedarville, CA. http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/fo/surprise/propRMP-FEIS.html (accessed May 15, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2007b. Tuledad Allotment 2007 Annual Operating Plan. Cedarville, CA. [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2011. Colorado Bighorn Sheep Occupied Habitat and Domestic Sheep Grazing Allotments. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/wo/ Planning_and_Renewable_ Resources/fish__wildlife_and/sheepmaps.Par.41042.File.dat/ BighornSheep_CO_26x34_v10. pdf (accessed November 17, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2012. Tobin Range Wilderness Study Area. N.p. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/nv/field_offices/winnemucca_field_office/

wsas.Par.94117.File.dat/Tobin%20Range.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Cassirer, E. Frances, Lloyd E. Oldenburg, Victor L. Coggins, Pat Fowler, Karen Rudolph, David L. Hunter, and William J. Foreyt. 1996. Overview and preliminary analysis of a bighorn sheep dieoff, Hells Canyon, 1995-96. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 10th Biennial Symposium, Silverthorne, CO, April 29-May 3.

Colorado Division of Wildlife (CDOW). 2009. Colorado Bighorn Sheep Management Plan: 2009-2019. Edited by J.L. George, R. Kahn, M.W. Miller, and B. Watkins. Denver. http:// wildlife.state.co.us/SiteCollectionDocuments/DOW/WildlifeSpecies/Mammals/Colorado BighornSheepManagementPlan2009-2019.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Crowser, Vivaca. 2011. News: Bighorn Lambs Still Feeling Effects of 2009-2010 Pneumonia Outbreak. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. ftp://www.co.missoula.mt.us/ ruralftp/Newsletter/LinksFrom-eNewsletters/2011-7_BighornLambs2010Pneumonia Outbreak.pdf (accessed May 13, 2012).

Cummings, Patrick J., and Craig Stevenson. 1995. Status of desert bighorn sheep in Nevada – 1994. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 39th Annual Meeting, Alpine, TX. April 5-7.

DeLong, Jeff. 2011. Disease killing off Nevada bighorn sheep. September 10. Reno Gazette-Journal. http://www.rgj.com/article/20110910/NEWS/109100308/Disease-killing-off-Nevada-bighorn-sheep?odyssey=mod|newswell|text|Local%20News|s (accessed September 13, 2011).

Desert Bighorn Council Technical Staff. 1990. Guidelines for the management of domestic sheep in the vicinity of desert bighorn habitat. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 34th Annual Meeting, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. April 4-6.

Dobel, Mike. 2012. Regional Supervising Biologist (Western Region), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. October 3.

Edwards, Victoria L., Jennifer Ramsey, Greg Jourdannais, Ray Vinkey, Michael Thompson, Neil Anderson, Tom Carlsen, and Chris Anderson. 2010. Situational agency response to four bighorn sheep die-offs in western Montana. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 17th Biennial Symposium, Hood River, OR. June 7-11.

Edwards, Vickie. 2012. Wildlife Biologist (Missoula Area), Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. August 7.

Epps, Clinton W., Vernon C. Bleich, John Wehausen, and Steven G. Torres. 2003. Status of bighorn sheep in California. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 47th Annual Meeting, St. George, UT. April 8-11.

Flores, Jr., Elias. 2012. Wildlife Biologist (Surprise District), Bureau of Land Management. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 28.

Foster, Craig. 2012. District Wildlife Biologist (Lakeview Field Office), Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 25.

Frisina, Michael R. 2012. Adjunct Professor of Range Sciences, Montana State University. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. July 23.

George, Janet L., Michael W. Miller, Gary C. White, and Jack Vayhinger. 1996. Comparison of mark-resight population size estimators for bighorn sheep in alpine and timbered habitats. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 10th Annual Symposium, Silverthorne, CO. April 29-May 3.

George, Janet L., Daniel J. Martin, Paul M. Lukacs, and Michael W. Miller. 2008. Epidemic Pasteurellosis in a bighorn sheep population coinciding with the appearance of a domestic sheep. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 44, no. 2 (April): 388-403.

George, Janet L. 2012. Senior Terrestrial Biologist (Northeast Region), Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. July 16.

Gibson, Steve. 2012. Rangeland Program Manager (Ochoco National Forest), U.S. Forest Service. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. August 15.

Jansen, Brian D., Paul R. Krausman, James R. Heffelfinger, Ted H. Noon, and James C. Devos, Jr. 2007. Population dynamics and behavior of bighorn sheep with infectious keratoconjunctivitus. Journal of Wildlife Management 71, no. 2 (April): 571-575.

Jeffress, Jim. 2012. Idaho Wild Sheep Foundation Chapter Board of Directors Member/ Retired Nevada Department of Wildlife Biologist (Western Region). Interview by author. Conducted by phone. June 12.

Joe Saval Co. v. Bureau of Land Management and State of Nevada, Department of Wildlife, Intervenor. 119 IBLA 202 (1991). http://www.oha.doi.gov/IBLA/Ibla decisions/119IBLA/ 119IBLA202%20JOE%20SAVAL%20CO.%20V.%20BLM,%20NEVADA%20%28APPELLANTS% 29%205-7-1991.pdf (accessed November 5, 2012).

Mack, Kurtis M. 2008. Wandering wild sheep policy: A theoretical review. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 16th Biennial Symposium, Midway, UT. April 27-May 1.

Missoula Parks and Recreation Department (MPRD). 2010. Appendix C: Bighorn Sheep and Domestic Sheep Interaction Protocol. In Missoula Conservation Lands Management Plan. http://www.ci.missoula.mt.us/DocumentCenter/Home/View/4499 (accessed January 4, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP). 1986. Bighorn Sheep Transplant Guidelines. N.p. [govt. doc.]

Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP). 2010. Montana Bighorn Sheep Conservation Strategy: 2010. Helena. http://fwpiis.mt.gov/content/getItem.aspx?id =397 46 (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Fish and Game (NDFG). 1978. The Desert bighorn sheep of Nevada. By Robert P. McQuivey. Reno, NV. [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2006. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2005-2006 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/biggame.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2007. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2006-2007 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/Big%20Game%20 Status%20Book_06_07.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2008. Bighorn Sheep Die-off in Hay’s Canyon: 2007/2008. N.p. http://www.ndow.org/wild/health/HaysCanyonDieOff2007.pdf (accessed December 18, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2010. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2009-2010 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/10_bg_status.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2012a. Mule Deer Hunter Information Sheet, See unit descriptions Unit 043, Unit 044, Unit 045, Unit 046. N.p. http://www.ndow.org/hunt/ resources/infosheets/deer/west/043_044_045_046deer.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2012b. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2011-2012 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/2012_Big%20

Game%20Status%20Book.pdf (accessed June 9, 2012).

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2012c. Nevada Department of Wildlife Management Units. http://ndow.org/hunt/maps/unitmap.shtm (accessed May 14, 2012).

Nevada Division of Wildlife (NDOW). 2001. Nevada Division of Wildlife’s Bighorn Sheep Management Plan: October 2001. Reno. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/plans/bighorn_ management_plan.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW). 1986. Oregon Bighorn Sheep Management Plan. N.p. [govt. doc.]

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW). 2003. Oregon’s Bighorn Sheep & Rocky Mountain Goat Management Plan: December 2003. Salem. http://www.dfw.state.or.us/ wildlife/management_plans/docs/sgplan_1203.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW). 2012. Bighorn Sheep Herd Composition, Fall and Spring 2011-2012. N.p. http://www.dfw.state.or.us/resources/hunting/big_game/ controlled_hunts/docs/hunt_statistics/12/BIGHORN_COMP_2012.pdf (accessed April 28, 2012).

Person, Daniel. 2009. FWP plan spooks woolgrowers. Bozeman Daily Chronicle. August 18. http://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/article_8ed64aa6-33b1-5067-9507-0ae209c87594.html (accessed January 7, 2012).

Reese, Rick. 1985. Montana mountain ranges. Helena: Montana Magazine, Inc.

Soletti, Scott. 2012. Wildlife Biologist (Surprise District), Bureau of Land Management. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 23.

Stockman, Karen. 2012. Biological Science Technician (Lolo National Forest), U.S. Forest Service. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 13.

Surian, Steve. 2012. Supervisory Rangeland Management Specialist (Surprise District), Bureau of Land Management. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 11.

Tanner, Gregg. 2012a. Retired Game Bureau Chief (Statewide), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. October 31.

Tanner, Gregg. 2012b. Retired Game Bureau Chief (Statewide), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. November 5.

The University of Montana (TUM). 2001. Appendix A: Letter from Fish, Wildlife and Parks regarding disease transmission from domestic to wild sheep. In Vegetation Management Plan for Selected Conservation Lands as adopted by Missoula City Council on 3/26/01. Missoula, MT. [govt. doc.]

Toweill, Dale E., and Valerius Geist. 1999. Return of royalty: Wild sheep of North America. Missoula, MT: Boone and Crockett Club and Foundation for North American Wild Sheep.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2000. Recovery Plan for Bighorn Sheep in the Peninsular Ranges, California. Portland. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/001025. pdf (accessed December 20, 2011). [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1984. Land and Resource Management Plan: Pike and San Isabel National Forests; Comanche and Cimarron National Grasslands. Pueblo, CO. http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/psicc/landmanagement/planning (accessed June 6, 2012). [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1986a. Forest Plan: Beaverhead National Forest. Dillon, MT. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1986b. The Lolo National Forest Plan. Missoula, MT. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1987. Forest Plan: Deerlodge National Forest. Butte, MT. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1988. Bearskull-Cottonwood Allotment Annual Operating Plan. Paulina, OR. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1989a. Bearskull-Cottonwood Allotment Annual Operating Plan. Paulina, OR. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1989b. Land and Resource Management Plan: Ochoco National Forest. Prineville, OR. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1990a. Final Environmental Impact Statement, Malheur National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan. N.p. [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1990b. Malheur National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan. N.p. http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/malheur/landmanagement/?cid=fsb dev3_033814 (accessed June 7, 2012). [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 2006. Risk Analysis of Disease Transmission Between Domestic Sheep and Bighorn Sheep on the Payette National Forest. McCall, ID. http://www.mwvcrc. org/bighorn/payette bighornreport.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 2007. Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis): A Technical Conservation Assessment, Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, February 12, 2007, by John J. Beecham, Cameron P. Collins, and Timothy D. Reynolds. Rigby, ID. http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/rockymountainbig hornsheep.pdf (accessed January 7, 2012). [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 2010a. Malheur National Forest: Review of Areas with Wilderness Potential. N.p. http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb526 0370.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012).

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 2010b. Appendix F: Best Management Practices Report, by Tim Schommer. In Southwest Idaho Ecogroup Land and Resource Management Plans – Update to the Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement – Boise National Forest, Payette National Forest, Sawtooth National Forest. McCall, ID. http://www.fs.usda.gov/ Internet/FSE_ DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5139347.pdf (accessed May 11, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Valliant, Morgan T. 2012. Conservation Lands Manager, Missoula Parks and Recreation Department. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. November 2.

Ward, A.C.S., D.L. Hunter, M.D. Jaworski, P.J. Benolkin, M.P. Dobel, J.B. Jeffress, and G.A. Tanner. 1997. Pasteurella spp. in sympatric bighorn and domestic sheep. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 33, no. 3 (July): 544-557.

Western Hunter. 2000. Bighorns in Warner Mountains? J & D Outdoor Communications. http://www.westernhunter.com/Pages/Vol02Issue26/bighorns.html (accessed May 31, 2012).

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agenices (WAFWA). 2009. WAFWA Wild Sheep Working Group 5/29/09 Teleconference (0900-1100) Notes. N.p.: WAFWA. http://www. wafwa.org/documents/wswg/wswgminutes052909.pdf (accessed July 13, 2012).

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA). 2010a. WAFWA Wild Sheep Working Group recommendations for domestic sheep and goat management in wild sheep habitat: July 21, 2010. N.p.: WAFWA. http://www.wafwa.org/documents/wswg/WSWG ManagementofDomesticSheepandGoatsinWildSheepHabitatReport.pdf (accessed May 17, 2012).

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA). 2010b. WAFWA Wild Sheep Working Group summary: Winter 2009-2010 bighorn sheep die-offs (3/16/10). Cheyenne: WAFWA. Web address no longer available (accessed August 23, 2010; based on file info).

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA). 2010c. WAFWA Wild Sheep Working Group teleconference: November 9, 2010 (10:00 am – Noon, MST). N.p.: WAFWA. http://www.wafwa.org/documents/wswg/wswg minutes11092010.pdf (accessed July 11, 2012).