Hays Canyon Range, NV: 2007

INTRODUCTION

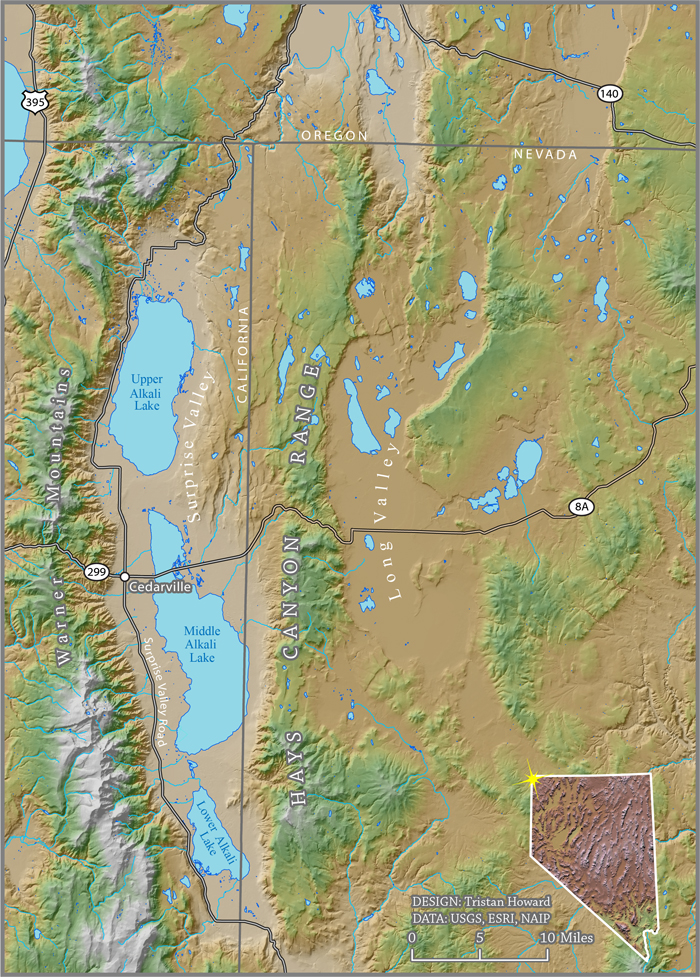

The Hays Canyon Range (41° 20’ 31.65”N, 119° 57’ 23.73”W) lies very near the California border in northwest Nevada’s Washoe County. It is located about 48 km (30 mi) east of Alturas, California (Google Earth 2012). According to the BLM’s 1995 mountain sheep ecosystem management strategy, the Hays Canyon Range bighorn habitat bioregion is 85 percent BLM land and 15 percent private land (BLM 1995).

Regarding the Hays Canyon Range, the Nevada Dpartment of Wildlife (NDOW) states: “The western front of the range rises dramatically from the high altitude alkali flats near Eagleville, CA, to its rugged peak at 7900 feet” (2008a, 1). Heavy tree cover exists in some northern portions of the range (NDOW 2008a). However, much of the mountains are sparsely vegetated (Google Earth 2012). The Hays Canyon Range is within the Surprise District of the BLM’s management scheme. According to the BLM, in this district, “dominant vegetation types include grasslands, Great Basin shrubs, sagebrush, mixed sage-western juniper, western juniper, conifer, and riparian formations” (BLM 2007a, 3-1). The Hays Canyon Range is near the Great Basin’s extreme western edge, which terminates at the Warner Mountains (BLM 2007a).

Surprise Valley in California separates (sometimes with as little as 11 km [7 mi] in some areas) the Hays Canyon Range from the adjacent Warner Mountains to the west (Google Earth 2012). The Warner Mountains hosted bighorns before Euro-American settlement and in the 1980s after reintroduction (Meintzer 2009). However, in 1988, a pneumonia-caused die-off (attributed to domestic sheep pathogens) completely wiped out the population (Bleich et al. 1990). The BLM notes that “in recent years, the lack of water in bighorn ranges has forced a few bighorn sheep [from the Hays Canyon Range] to cross over to the Warner Mountains” (BLM 2007a, 3-117).

A population of California bighorns was reestablished in the Hays Canyon Range in 1989 (NDOW 2008a). The new population expanded in size and distribution, which brought them closer to domestic sheep (NDOW 2006). In 2007, thousands of domestic sheep were authorized to graze on a BLM allotment located along the southern part of the Hays Canyon Range (BLM 2007a, b). Nearby domestic sheep also existed on private lands (Surian 2012). In 2007, a pneumonia outbreak terminated the existence of bighorns in the Hays Canyon Range (NDOW 2008a; Dobel 2012a). Important policy documents applied to the Hays Canyon Range in 2007 and directly addressed the wild-domestic sheep disease problem. These documents include a 2007 BLM proposed resource management plan, the BLM’s 1998 guidelines for managing domestic sheep and goats in wild sheep habitat, and NDOW’s 2001 bighorn management plan (BLM 2007a, 1999; NDOW 2001).

Concerning particular bighorn-domestic sheep interaction policies, just prior to its wild sheep die-off, the Hays Canyon Range lacked buffers, sheepherder supervision rules, and trailing restrictions (Flores, Jr. 2012). Nonetheless, domestic sheep presence was considered before bighorn reintroduction, grazing allotment alteration was implemented, negotiation and education occurred, and at least one bighorn near domestic sheep was removed from the wild (Flores, Jr. 2012; Epps et al. 2003). Additionally, both coordination and tension existed between agencies, and funding difficulties were not an issue (BLM 2007a; NDOW 2001; Soletti 2012; Flores, Jr. 2012; Dobel 2012a). Before specifically analyzing policies that influenced bighorn-domestic sheep interaction in the Hays Canyon Range, it helps to have some history on the area’s bighorns before pneumonia extirpated them.

BIGHORN POPULATION HISTORY PRIOR TO OUTBREAK

In December 1989, wildlife managers transplanted 15 California bighorns to the Hays Canyon Range from Williams Lake, British Columbia. In 1995, the population was augmented with an additional 15 animals from northwest Nevada’s Jackson and Santa Rosa Mountains (NDOW 2008a). The NDOW provides a Hays Canyon Range bighorn population history prior to the outbreak:

“Production and recruitment levels for the . . . bighorn herd have been very good since they were first released . . . . The herd has averaged 56 lambs per 100 ewes since that time. In recent years the observed lamb ratio has been even higher. This has allowed the population to continue to expand in both number and distribution. Recent observations of bighorn in the southern portion of the Hays Canyon Range are further proof that this herd continues to do well and that the herd is expanding into other good quality sheep habitats that are available. However, there is increasing concern with escalating domestic goat and sheep operations . . . and the potential for interaction with our wild sheep population” (2006, 69-70).

The NDOW remarks that “at one point, [the Hays Canyon Range population] was considered to have among the highest ewe to lamb ratios in Washoe County” (2008a, 1). An estimated 110 bighorns inhabited the Hays Canyon Range in 2006-2007 (NDOW 2008a). Although the Hays Canyon Range hosted many bighorns by the early twenty-first century, they may have been greatly out-numbered by nearby domestic sheep.

NEARBY DOMESTIC SHEEP

According to the BLM’s May 2007 Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Surprise District (Surprise PRMP): “Grazing of domestic sheep would continue on the Tuledad, Selic-Alaska, and Red Rock Lake allotments” (BLM 2007a, 2-37). In 2007, these were the only allotments near the Hays Canyon Range containing domestic sheep (BLM 2007a). According to BLM biologist Scott Soletti: “The allotments that contained bighorn sheep were cattle grazing only allotments” (2012).

In 2007, the Selic-Alaska and Red Rock Lake allotments were located west of the Warner Mountains in California, so their domestic sheep may not have posed a significant threat to bighorns because of topography. However, the Tuledad Allotment was located along the southern portion of the Hays Canyon Range, so domestic sheep may well have been near bighorns at the time of the outbreak (BLM 2007a). In 2007, the Tuledad Allotment hosted five cattle operators and one operator who ran both cattle and sheep. For sheep, the BLM permitted 2,352 AUMs on the allotment in 2007 (BLM 2007b).

According to the BLM, “an AUM is the amount of forage needed to feed a cow, one horse or five sheep for one month” (2011). Pratt and Rasmussen provide a more complete definition:

“The animal unit month (AUM) concept is the most widely used way to determine the carrying capacity of grazing animals on rangelands. The AUM provides us with the approximate amount of forage a 1000 lb cow with calf will eat in one month. It was standardized to the 1000 lb cow with calf when they were the most prevalent on rangeland. This AUM was established to be 800 lbs of forage on a dry weight basis (not green weight). All other animals were than converted to an “Animal Unit Equivalent” of this cow. For example, a mature sheep has an Animal Unit Equivalent of 0.20. This means a sheep eats about 20% of the forage a cow will eat in one month” (2001).

This definition indicates the BLM allowed 11,760 (5 x 2,352) domestic sheep to graze on the Tuledad Allotment in 2007.

The NDOW confirmed the nearby presence of domestic sheep in its 2005-2006 state big game status report where it stated: “Domestic sheep trailing routes and grazing areas are . . . located in the valley bottoms surrounding the southern portions of the Hays Canyon Range. As this bighorn population expands, the likelihood for a disease related die-off due to interactions with domestic sheep or goats increases” (2006, 70). The NDOW repeated such concerns in its 2006-2007 status report in which it stated: “The movement of bighorn to the south-end of the range puts the bighorn closer to domestic sheep grazing and trailing routes and increases the likelihood of nose to nose contact” (2007, 72).

Regarding the Hays Canyon Range disease outbreak, in June 2012, Steve Surian (the BLM’s Supervisory Rangeland Management Specialist for the Surprise District) stated that “there [have] been discussions (rumors) [that] the source of the epizootic may have been from goats and/or domestic sheep located on private lands near Farmers springs, which is located between 49 Mountain and Bull Creek, east of Cedarville” (2012).

The history of domestic sheep in the Hays Canyon Range area is dynamic. The NDOW’s Western Region Supervising Biologist Mike Dobel provides the important insights that follow. According to Dobel, the Tuledad Allotment was active in 1989 at the time of the original transplant. However, in 1989, domestic sheep used a different part of the allotment than they used in 2007 when the outbreak happened. There were also a number of years when nobody used the Tuledad Allotment to graze domestic sheep. For some time, the Tuledad Allotment was also used mainly for trailing sheep, and they were trailed pretty far south of bighorn range. Nonetheless, there were sightings of bighorn rams entering the Tuledad Allotment (Dobel 2012a).

At least two different livestock operators used the Tuledad Allotment after bighorns were reintroduced to the area in 1989. At one point, one sheep operator bought out another. The new operator grazed domestic sheep much closer to bighorns than they had ever been before. He began wintering his sheep at the south end of the Hays Canyon Range. He was also uncooperative, stubborn, and uncommunicative. He did not have a good relationship with NDOW or the BLM. Furthermore, he did not believe domestic sheep posed a disease risk to bighorns. This operator substantially increased the area’s wild-domestic sheep disease transmission risk factor (Dobel 2012a).

Back when wild sheep roamed the Hays Canyon Range, Nevada had an estray livestock law which precluded NDOW from shooting stray domestic sheep to remove their threat to bighorns. To legally remove domestic sheep, NDOW had to seek permission from the State Department of Agriculture and the permittee responsible for the stray sheep. This led to live-capturing and net-gunning of domestic sheep. The NDOW put significant effort into capturing domestic sheep alive. This was partly to take samples from domestic sheep to test for disease and aid with research efforts. Live removals of domestic sheep were also part of an attempt to clear the range and reduce the domestic disease threat. Live-capture of domestic sheep occurred in the Hays Canyon Range area and many other areas across the state (Tanner 2012a, b). Despite the preventative efforts of Nevada’s wildlife biologists, domestic sheep may well have caused a devastating bighorn pneumonia outbreak in 2007.

OUTBREAK SUMMARY

The Hays Canyon Range bighorn pneumonia outbreak seems to have primarily struck in late summer, fall, and early winter of 2007 (NDOW 2008a). Nevada Bighorns unlimited (NBU)—a bighorn advocacy group—cooperated with NDOW in investigating this die-off (NBU 2011; NDOW 2008a). The NDOW presents a summary of the Hays Canyon Range pneumonia epizootic:

“The news of a possible disease event in this area came from a 2007 bighorn sheep tag-holder. While driving into Hay’s Canyon [in early October] he observed what appeared to be a sick ewe bedded down under a tree close to the road; the same animal was found dead a few hours later. NDOW Law Enforcement followed up on his report and helped retrieve the carcass which was then transported to Reno for veterinary diagnostic work-up and a thorough necropsy examination. The results of the examination, backed up by various laboratory results, confirmed that the ewe died from severe bacterial pneumonia. Both Biebersteinia (formerly Pasteurella) trehalosi and a common pus-forming bacterium, Arcanobacterium, were cultured from the lesions in the lungs. The ewe also showed scarring in the lungs that suggested Mycoplasma infection (Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae). This particular species of Mycoplasma was implicated in the deaths of bighorn sheep in Idaho, Washington and Oregon in 2006, although in that instance, a host of other factors probably were involved.

NDOW performed an intensive follow-up aerial survey of the Hay’s Canyon area (sponsored by NBU, Reno) immediately following the discovery of the first dead ewe. Only seven live sheep were seen. Increasingly intensive ground surveys in October and November followed and during this time, NDOW biologists and dedicated NBU members spent time in the mountains on foot and were able to locate several decomposed carcasses as well as several sick bighorn sheep. Through the cooperation of NDOW and NBU, a number of valuable samples were obtained from both sick and dead animals.

As expected, bacterial pneumonia was identified in all animals but a very interesting finding consistent among many of these animals was that the pneumonia was apparently caused by Pasteurella multocida U6. Pasteurella is one class of bacteria commonly seen in sheep with pneumonia and it’s been well established that certain species can cause disease in bighorns. The species P. multocida however is not ordinarily associated with disease in bighorn sheep, but this particular biotype is known to have been a factor in other bighorn die-offs in other areas. For example, the same bug was cultured in high numbers from free-ranging bighorn sheep in the Hells Canyon area of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon during the winter of 1995-96 following a major die-off. Animals captured in Hells Canyon and held in captivity, and their offspring, also harbored P. multocida U6.

All evidence gathered in the fall of 2007 pointed to a die-off occurring in the area and a second helicopter survey was conducted by NDOW in mid-November covering the entire ridge system and western slope of the Hay’s Canyon Range. The survey turned up more carcasses and only two bighorn were seen alive. Several bighorn observed alive during the initial helicopter survey in October were later found dead near or adjacent to water sources.

Additional ground surveys failed to locate any live bighorn; however, three sets of fresh bighorn tracks were observed near the lower big game guzzler in late November. As a result, a remote camera was positioned at the guzzler in an attempt to document the presence of live bighorn; unfortunately, none was photographed during the 5 to 6 week period of observation. Ground surveys continued and focused on south slopes, open areas, and water sources on the western slope of the Hays Canyon Range. No live bighorn were observed but additional carcasses were located including the skull and remains of a 9-year-old ram located by a rancher near a spring source in early December” (NDOW 2008a, 1-2).

A detailed NDOW report on the Hays Canyon Range disease outbreak (quoted above) makes no reference to domestic sheep (2008a). However, in a March 2008 report, an NDOW veterinarian mentions that grazing permit holders were participating in the disease investigation (NDOW 2008b).

The NDOW indicated the pneumonia causal mechanism was a mystery and stated: “Unfortunately it may be some time before we have a good understanding of the factors that initiated this disease event . . . . Respiratory disease in bighorn sheep is especially complex, usually involves multiple factors and specific causes can be very difficult to determine” (2008a, 3). They added: “We hope soon to be able to shed light on what may have contributed to these disease events. Since early spring, ground investigations have taken place and several reliable reports of a small number of live bighorn sheep have been received” (2008a, 3).

In its 2007-2008 big game status report, NDOW stated: “It is still possible that there are bighorn that survived the disease event” (NDOW 2008c, 80). However, in its status reports published from 2009-2012, NDOW neglected to even mention the Hays Canyon Range (NDOW 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012a). As of 2012, there had been no confirmed, documented sightings of bighorns in the Hays Canyon Range since the 2007 die-off (Dobel 2012a).

Things looked grim, but in January 2013, NDOW transplanted 30 bighorns from Nevada's Pine Forest Range into the Hays Canyon Range (NDOW 2013). An NDOW report on 2012-2013 bighorn restoration efforts touches on the Hays Canyon Range die-off and applauds the bighorn-domestic sheep interaction mitigation work of big game biologist Chris Hampson:

“The Hays Canyon Range has had its ups and downs in the past. The entire Hays Canyon Range bighorn herd had died during a severe pneumonia event in 2007 where we lost over 110 bighorn. Sifting through the ashes, Chris Hampson worked tirelessly with the California BLM Surprise Field Office to assess and eventually remove the threat of future disease transmission from private domestic sheep/goat flocks adjacent to the mountain range. Hats off to Chris and his BLM counterparts for being diligent and changing the status quo to allow for bighorn restoration in the Hays Canyon Range” (2013, 4-5).

An examination of policy documents reveals insights on regulations that may have prevented the obliteration of the Hays Canyon Range’s bighorns if they were followed more closely.

POLICY DOCUMENTS

The BLM’s May 2007 Surprise PRMP describes many wild-domestic sheep interaction policies applicable on a location-specific level to the Hays Canyon Range (BLM 2007a). This document was completed just prior to the fall 2007 pneumonia outbreak, so it provides insights on agency tendencies at the time. However, a record of decision (ROD) for that PRMP was not published until April 2008 (BLM 2008). The ROD “links final land use plan decisions to the analysis presented in the Proposed RMP/Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS)” (BLM 2008, 2).

One item that stands out in the PRMP (and contrasts with reputable scientific consensus) is a response to a public comment questioning the validity of the concept of domestic sheep transmitting disease to bighorns. Part of the BLM’s response was: “The scientific evidence regarding the susceptibility of bighorn sheep to disease transmitted by domestic sheep is still open for debate” (BLM 2007a, A-139).

Additionally, the PRMP states that the “BLM’s [1998] Revised Guidelines for Managing Domestic Sheep and Goats in Wild Sheep Habitats . . . would provide operational guidance for domestic sheep and goat management in the SFO [Surprise Field Office]” (2007a, 2-37). The PRMP also states that “regarding elimination of domestic sheep in areas used by bighorn sheep,” the BLM will use those guidelines (BLM 2007a, A-249). A BLM resource management plan for the Challis area in Idaho provides background on the 1998 guidelines:

“These guidelines . . . were included as Attachment 1 to BLM Instruction Memorandum No. 98-140 (July 10, 1998). The 1998 revised guidelines were developed following a review of the 1992 Guidelines for Domestic Sheep Management in Bighorn Sheep Habitats (Instruction Memorandum 92-264) in June 1997, and a follow-up meeting of bighorn and domestic sheep specialists in April 1998. Instruction Memorandum 98-140 state that these revised guidelines ‘should be followed whenever reintroductions, transplants, or augmentations of wild sheep populations, or proposed changes in a livestock grazing permit on BLM administered lands are being considered. . . ’” (BLM 1999, 95).

Within the 1998 guidelines, the BLM added language providing enforcement flexibility:

“. . . the guidelines . . . should be followed in current and future native wild/domestic sheep and goat use areas unless a specific cooperative agreement that includes the State wildlife management agency, the BLM and the livestock permit holder is in place. When such agreement is in place, the agencies and the livestock permit holder will be held harmless in the event of a disease impacting either native wild sheep or domestic sheep and goats” (BLM 1999, 95-96).

According to BLM biologist Scott Soletti: “A cooperative agreement was not in place for domestic sheep trailing in the Tuledad Allotment” (2012). Thus, management of the Tuledad domestic sheep should have followed the 1998 BLM guidelines.

The NDOW’s Bighorn Sheep Management Plan: October 2001 is the main document pertinent to state wildlife agency policies in place at the time of the Hays Canyon Range outbreak (NDOW 2001). According to NDOW, that plan “is a guiding document for the Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners . . . and the Nevada Division of Wildlife . . . efforts in the conservation and management of bighorn sheep populations and their habitat” (2001, 2). Several NDOW plan statements are relevant to all policy analysis criteria in this study (2001).

One such statement is NDOW’s declaration that: “Domestic sheep operations pose the largest obstacle to the further expansion of bighorn sheep populations in the State of Nevada due to continued concerns over disease transmission” (2001, 8). The NDOW also remarks that: “The Division will encourage and support the management of livestock when such management results in the attainment of land use goals and objectives consistent with wildlife needs. The Division should take appropriate action, including litigation, when these goals and objectives are not obtained” (2001, 12). The NDOW adds: “The Division will minimize domestic farm flock sheep/wild sheep interactions through all possible means. This could include entering into cooperative agreements with willing landowners, education, and cooperating with [the] Department of Agriculture” (2001, 21).

The NDOW did not state that it will adhere to or adopt the BLM’s 1998 guidelines, but the guidelines are listed in the plan’s “Appendix A: Laws and Regulations Pertinent to Bighorn Sheep Management” (2001, A-3). The NDOW also says it “may initiate a disease prevention or health enhancement program for a particular [bighorn] population if the costs and benefits are justified” (2001, 21). Additionally, regarding disease management strategies, NDOW states that “The Bighorn Sheep Interaction With Domestic Sheep and Disease and Health Assessment protocols will be followed” (2001, 21).

Now that background has been provided on the 2007 Hays Canyon Range bighorn disease outbreak and numerous factors related to it, context has been established for more fully understanding specific wild-domestic sheep policies in the area.

POLICY ANALYSIS CRITERIA

1.) Were clearly defined buffer zones established to ensure separation of bighorns and domestic sheep?

Answer and Explanation

In the Hays Canyon Range, clearly defined buffer zones were not established in an effort to separate bighorns and domestic sheep (Flores, Jr. 2012). Bureau of Land Management biologist Elias Flores, Jr. explains why the Surprise District did not have clearly defined buffers in 2007:

“There were no ‘clearly defined’ buffer zones in place. They are not required if adequate separation obstacles or distances or timing exists. Three allotments on the field office; Tuledad, Selic/Alaska, and Red Rock Lake are authorized for domestic sheep grazing. I had asked that the permittees inform the BLM when they would be trailing through the Tuledad allotment however it doesn’t look like it made it into the official, signed Annual Operating Plan. Without a large buffer distance, domestic and bighorn sheep could theoretically make nose to nose contact between the Tuledad and Duck Lake and Lower allotments (these last two being known bighorn areas) if domestic sheep were not closely watched and bighorn were in the area” (2012).

At the time of the 1989 establishment of bighorns in the Hays Canyon Range, there was no need for any type of agreement on buffers because bighorn range was isolated enough from domestic sheep that managers assumed a disease threat was not significant. In 1989, the Hays Canyon Range also hosted no active domestic sheep allotments (Dobel 2012a).

Policy

According to the BLM’s 1998 guidelines, “native wild sheep and domestic sheep or goats should be spatially separated to reduce the potential of interspecies contact” (1999, 96). The BLM also remarks:

“In reviewing new domestic sheep or goat grazing permit applications or proposed conversions of cattle permits to sheep or goat permits in areas with established native wild sheep populations, buffer strips surrounding native wild sheep habitat should be developed, except where topographic features or other barriers minimize physical contact between native wild sheep and domestic sheep and goats. Buffer strips could range up to 13.5 kilometers (9 miles) or as developed through a cooperative agreement to minimize contact between native wild sheep and domestic sheep and goats, depending upon local conditions and management options” (BLM 1999, 96).

In the 2007 Surprise PRMP, a “No Action Alternative” in a table regarding noxious and invasive weeds states: “A minimum nine mile buffer (or as developed through a cooperative agreement) between domestic sheep, goats and bighorn habitat would continue to limit the use of sheep and goats as weed control agents . . .” (BLM 2007a, 2-144). In its 2006-2007 big game status report, regarding the Hays Canyon Range, NDOW states: “Future water developments built on the top of the rim will help keep bighorn away from the valley bottoms where domestic sheep are grazed and trailed” (2007, 72).

2.) Were special supervision rules in place for sheepherders?

Answer and Explanation

No location-specific special supervision rules existed that would encourage sheepherders to keep their flocks separate from bighorns (Flores, Jr. 2012). Flores, Jr. notes: “There is disagreement as to whether domestic sheep always have herders with them however on several occasions domestic sheep have been observed by both BLM and [NDOW] with no sheep herders” (2012). Dobel emphasized that domestic sheep can unexpectedly show up in certain areas (2012a).

Policy

The BLM’s 1998 guidelines state: “Domestic sheep and goats should be closely managed and carefully herded where necessary to prevent them from straying into native wild sheep areas” (1999, 96). The BLM adds: “Cooperative efforts should be undertaken to quickly notify the permittee and appropriate agency to remove any stray domestic sheep or goats or wild sheep in areas that would allow contact between domestic sheep or goats and native wild sheep” (1999, 96).

3.) Were domestic sheep trailing restrictions in place to ensure separation?

Answer and Explanation

No domestic sheep trailing restrictions were in place to ensure wild-domestic sheep separation (Flores, Jr. 2012). The BLM’s 2007 operating instructions for the closest domestic sheep grazing allotment did not mention special trailing restrictions related to protecting bighorns (2007b). However, as mentioned in the explanation to criterion #1, the BLM did ask for notification for when domestic sheep trailing near bighorn habitat would occur (Flores, Jr. 2012).

Policy

The BLM’s 1998 guidelines state: “Domestic sheep or goat grazing and trailing should be discouraged in the vicinity of native wild sheep ranges” (1999, 96). The BLM adds: “Trailing of domestic sheep or goats near or through occupied native wild sheep ranges may be permitted when safeguards can be implemented to adequately prevent physical contact between native wild sheep and domestic sheep or goats. BLM must conduct on-site use compliance during trailing to ensure safeguards are observed” (1999, 96).

At a BLM national policy level, NDOW participated in policymaking in which it was decided that BLM employees would monitor domestic sheep trailing to reduce the risk of disease transmission to bighorns. Such policy is quoted above. This policy (introduced in the early 1990s) was an attempt to pacify state game agencies. Unfortunately, the policy did not have legal teeth, and according to at least one retired NDOW Game Bureau Chief, it was never enforced (Tanner 2012a). This correlates with the fact that the 2007 Tuledad Allotment operating instructions document makes no reference to special accommodations for bighorns in its directions for monitoring, trailing, or general sheep pasture use (BLM 2007b).

The Surprise PRMP says: “Trailing may be allowed in allotments closed to domestic sheep grazing in compliance with BLM’s ‘Guidelines for Managing Domestic Sheep and Goats in Wild Sheep Habitats’” (BLM 2007a, 2-37). In a table describing domestic sheep grazing alternatives, for a “No Action Alternative” (current policy at the time of the Hays Canyon Range outbreak), the Surprise PRMP states that trailing of domestic sheep would be allowed “in [the] Tuledad, Selic-Alaska, and Red Rock Lake Allotments and in areas that are allotments ≥ 9 miles from occupied bighorn habitat” (BLM 2007a, 2-124).

4.) Were policies in place or was consideration taken regarding the concept of prohibiting bighorn reintroduction to the site if it hosted domestic sheep?

Answer and Implementation

Domestic sheep presence was directly addressed before bighorn reintroduction (Flores, Jr. 2012). Flores, Jr. explains how considerations were addressed prior to reintroducing bighorns to the Hays Canyon Range:

“A Habitat Management Plan was developed (1989) between BLM, NDOW, Nevada Bighorn’s Unlimited and several local ranchers. Several factors including the die-off in early 1988 of bighorn in the Warner Mountains, led to the recommendation of reintroducing bighorn sheep into the entire Hays Range. The 1988 recommendation came about through a task force appointed by the Modoc/Washoe Experimental Stewardship Steering Committee” (2012).

Policy

Prior to the 1989 reintroduction of bighorns to the Hays Canyon Range, there was an internal NDOW policy not to release bighorns into areas hosting domestic sheep (Tanner 2012a).

5.) Before the disease outbreak, was any effort made to buy out nearby domestic sheep grazing allotments or convert them to cattle?

Answer and Implementation

One sheep allotment was converted to cattle (Flores, Jr. 2012). Flores, Jr. states: “Part of the task force [appointed by the Modoc/Washoe Experimental Stewardship Steering Committee prior to bighorn reintroduction] recommendation was that BLM convert sheep AUMs to cattle AUMs in the Bicondoa Allotment (Hays Range)” (2012). An examination of the latest Surprise PRMP shows that the Bicondoa Allotment was no longer a sheep allotment by 2007 (BLM 2007a).

Policy

The Surprise PRMP declares: “Voluntary changes or conversions of the permits from domestic sheep to cattle grazing provide the Surprise Field Office the opportunity to coordinate with state wildlife agencies and other cooperators in developing a reintroduction plan for California bighorn sheep prior to reintroduction efforts” (BLM 2007a, 2-37). The PRMP also remarks:

“Grazing of domestic sheep would continue . . . unless in the future the current operator elects to convert the livestock kind from sheep to cattle or if the allotments are vacated for reasons unforeseeable at this time. Due to the interest of state game agencies to reintroduce bighorn back into the Warner Mountains, any subsequent request to convert permits from cattle back to sheep would be coordinated with livestock operators and state game agencies” (BLM 2007a, 2-37).

The Surprise PRMP would allow conversion of cattle allotments to sheep allotments “if [there is] low potential for direct contact between domestic sheep and bighorn” (BLM 2007a, 2-124).

The NDOW’s bighorn management plan states: “The purchase of conservation easements, property and associated grazing privileges, conversions of Animal Unit Months (AUM’s) from domestic sheep to cattle or water rights, will be done to protect or enhance important bighorn sheep habitat” (2001, 2). Further in the plan, NDOW uses somewhat looser language (“pursue” instead of “done”) in a nearly identical statement (2001, 8). The NDOW adds: “Any AUM conversion, acquisition of private land, grazing privileges or easements will only be accomplished through a willing seller. The purchase of conservation easements and AUM conversions would be preferred over the purchase of property” (2001, 8).

6.) Were other forms of negotiation and/or education attempted with local stakeholders regarding the issue of bighorn-domestic sheep disease transmission?

Answer and Implementation

Negotiation and education were attempted with local stakeholders, but such efforts were not always successful (Flores, Jr. 2012). Flores, Jr. notes that “any information has been met with great criticism. There is still local belief by producers that there is no issue of disease transfer between domestic sheep and bighorn sheep” (2012). Some of the livestock operators in the Hays Canyon Range area are especially irrational, and talking to them can be difficult. The NDOW engaged in cooperative efforts with the BLM in attempts to talk to livestock operators about the disease threat of domestic sheep. However, some forms of cooperation are at the will of particular stakeholders. There is only so much that agencies can do. Nonetheless, NDOW has had a pretty good working relationship with some sheep ranchers, including those who have owned sheep that got net-gunned and relocated by NDOW (Dobel 2012a).

Policy

In its bighorn management plan, NDOW regularly emphasizes the need for more public education on bighorns (2001). It remarks:

“The desert bighorn sheep is Nevada’s state animal; yet, the general public has very little knowledge about bighorn sheep. Therefore, the Division is challenged to increase public awareness and appreciation for bighorn sheep and their habitats in order to facilitate decisions favorable to their long-term well being” (NDOW 2001, 2).

The NDOW lists a management action to: “Continue to use all of the means available to educate the general public on issues pertaining to bighorn sheep and other wildlife” (2001, 29). It highlights a need for education to achieve both awareness and regulation compliance. The NDOW’s bighorn education policies target students, the general public, and hunters (2001).

7.) If wandering bighorns got too close to domestic sheep, were they ever removed from the wild in or near this location?

Answer and Implementation

In 2000, this policy was implemented in northeastern California’s Warner Mountains when a young bighorn ram was killed after he was seen with a group of domestic sheep (Meintzer 2009; Epps et al. 2003; Western Hunter 2000). This ram may have traveled from the Hays Canyon Range (BLM 2007a). Flores, Jr. was not aware of additional similar bighorn removals in the area (2012). Dobel also did not know of any more bighorn removal efforts in the Hays Canyon Range region. He noted that such removal was not really considered an option until recently (within the last five to six years) (2012a).

Policy

According to the BLM’s 1998 guidelines: “Cooperative efforts should be undertaken to quickly notify the permittee and appropriate agency to remove any stray domestic sheep or goats or wild sheep in areas that would allow contact. . .” (1999, 96). As of 2008, NDOW endorsed the wandering wild sheep removal policy (Mack 2008).

8.) Did coordination and/or tension exist between different levels (federal, state, local) of government management agencies regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction?

Answer and Nature

Both coordination and tension existed (BLM 2007a; NDOW 2001; Soletti 2012; Flores, Jr. 2012). Some tension existed onsite. Regarding the Tuledad Allotment, Soletti stated that “in general there was a struggle to organize and maintain communications between the permittee and the BLM in regards to trailing sheep” (2012). Flores, Jr. provides more detail regarding onsite agency tensions:

“There were differences of opinion during the RMP process as to where bighorn sheep should be. The California Department of Fish and Game had reservations concerning keeping domestic sheep in the three allotments listed above. Our guidance however is that BLM lands are to be managed for multiple resources. Having allotments open to both domestic and bighorn sheep falls within our multiple use mandates. In addition the BLM did not feel that having bighorn sheep in the south Warner Mountains was supportable given the number of domestic sheep in Modoc and Lassen counties as well as in Surprise Valley (also includes Washoe County). Also there had been a previous die-off (see above) and there were no other bighorn sheep populations in the general vicinity. NDOW generally supported the RMP but was in favor of modifying or removing the sheep permits to better protect bighorn in the Hays Range” (2012).

Coordination and tension also existed at the state level before the die-off. In the answers to a questionnaire presented to biologists at the 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference in 1999, Craig Mortimore provides details on California bighorn management in Nevada (Arthur et al. 1999). One question specifically regarding California bighorn management asks: “What are the 3 biggest challenges in your state/province regarding state/federal relationships and management of wild sheep?” (Arthur et al. 1999, 432). In response, Mortimore remarks that “NDOW has good relationships with USFS, USFWS, and BLM,” but he also lists “domestic sheep trailing” as a challenge (Arthur et al. 1999, 432).

Policy

The Surprise PRMP policy mentions that allotment conversions would give the BLM the “opportunity to coordinate with state wildlife agencies and other cooperators” (BLM 2007a, 2-37). The PRMP also mentions cooperating “with state game agencies in construction of additional guzzlers east of Surprise Valley to discourage bighorn sheep from crossing to the Warner Mountains” (BLM 2007a, 2-123).

More references to coordination occur in the BLM’s 1998 guidelines, which note that: “State wildlife and Federal land management agencies, native wild sheep interest groups, and domestic sheep and goat industry cooperation and consultation are necessary to maintain and/or expand native wild sheep numbers” (1999, 96). The BLM also indicated that their 1998 guidelines do not have to be followed if “a specific cooperative agreement that includes the State wildlife management agency, the BLM and the livestock permit holder is in place” (BLM 2007a, 95).

In its 2001 bighorn management plan, NDOW states: “Since most . . . bighorn sheep habitat is managed by the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, military installations, Indian Tribes, and private landowners, it is imperative that the Division always strive for cooperation and collaboration with these entities” (2001, 6).

9.) Did you encounter funding difficulties regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction management?

Answer and Nature

Funding difficulties were not in issue in the area (Flores, Jr. 2012; Dobel 2012a). Dobel could not recall any funding difficulties regarding wild-domestic sheep management in the Hays Canyon Range. He emphasized that within the realm of the disease issue, politics is more important than money (2012a). Flores, Jr. explains the nature of funding bighorn management in the Hays Canyon Range:

“There have been no projects brought forth by the BLM (other than habitat projects) that would require additional funding. BLM has worked with NDOW to support building/maintenance of bighorn sheep guzzlers or to have guzzlers filled during drier seasons. The BLM is currently working with NDOW to identify areas for fencing to reduce the possibility of contact between domestic and bighorn sheep. The BLM has acquired additional bighorn habitat through acquisition funding however these were not specifically for bighorn sheep. The BLM does not anticipate funding difficulties related to bighorn sheep” (2012).

Policy

Regarding bighorn habitat acquisition, land protection, and grazing allotment conversions, NDOW stated in its bighorn management plan that: “Funding sources could include mitigation from urban sprawl (such as Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act), conservation organization partnerships, heritage account, bond revenues and federal aid” (2001, 8).

POLICY EFFICACY SUMMARY

Regarding the wild-domestic sheep management situation in the Hays Canyon Range prior to 2007, agency neglect and ineffective policy implementation stand out. Location-specific bighorn-domestic sheep interaction policies actually implemented before the 2007 die-off did not include clear buffers, special sheepherder supervision rules, or trailing restrictions (Flores, Jr. 2012). However, all these policies were in print before the outbreak (BLM 1999) and could have been applied to the Hays Canyon Range. The fact that the BLM chose not to enforce these policies reflects ineffective handling of policies that may have been effective if they were actually implemented.

The consideration of domestic sheep before bighorn reintroduction and the alteration of a grazing allotment (Flores, Jr. 2012) reflect some policy efficacy and may have delayed a bighorn die-off in the Hays Canyon Range. However, domestic sheep consideration and grazing allotment alteration were too limited in scope, which made such policies ineffective in the long-term. Education and negotiation were attempted (Flores, Jr. 2012), but they were largely ineffective because of science denial from local sheep producers. In 2000, one bighorn (likely from the Hays Canyon Range) was removed from the wild after being seen near domestic sheep (Meintzer 2009; Epps et al. 2003; Western Hunter 2000). This removal may have been effective at delaying disease.

Coordination and tension were involved with managing Hays Canyon Range sheep. During the planning process for reintroducing sheep to the range, conflict existed between the BLM (which wanted to continue domestic sheep grazing in the area) and CDFG and NDOW (which had some bighorn-related concerns regarding nearby domestic sheep allotments) (Flores, Jr. 2012). This conflict contributed to the imperilment of Hays Canyon Range bighorns. It also illustrates wildlife federalism complications making policy more ineffective because it shows that in some instances, state governments may be more apt to take actions that are in the best interest of bighorns while federal agencies may disagree and supersede state preferences with harmful policies. If CDFG and NDOW had more influence over the BLM, or if better cooperation occurred, domestic sheep may not have been grazed on the Tuledad Allotment after bighorns were reintroduced, which could have prevented a die-off. Considering the fact that thousands of domestic sheep were authorized to graze near the Hays Canyon Range (BLM 2007b), a bighorn die-off seemed all but uncertain. In the Hays Canyon Range, politics proved to be a stronger influence on policy than funding, which was not a significant issue (Dobel 2012a).

REFERENCES

Arthur, Steven M., Ian Hatter, Alasdair Veitch, John Nagy, Jean Carey, Jon T. Jorgenson, Raymond Lee, John Ellenberger, John Beecham, John J. McCarthy, Gary Schlichtemeier, Larry T. Gilbertson, Bill Dunn, Don Whittaker, Ted A. Benzon, Jim Karpowitz, George Tsukamato, Kevin Hurley, Steven G. Torres, Craig Mortimore, Mike Oehler, Patrick Cummings, Craig Stevenson, Eric Rominger, and Doug Humphreys. 1999. Appendix A: Wild sheep status questionnaires. In proceedings of 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference, Reno, NV. April 6-9.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1995. Mountain Sheep Ecosystem Management Strategy in the 11 Western States and Alaska. N.p. ftp://ftp.blm.gov/pub/blmlibrary/BLM publications/StrategicPlans/Wildlife/ MountainSheepEcosystem.pdf (accessed May 11, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1999. Attachment 7: 1998 Revised Guidelines for Domestic Sheep and Goat Management in Native Wild Sheep Habitats. In Challis Resource Management Area: Record of Decision and Resource Management Plan. Salmon, ID. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/id/plans/challis_rmp.Par.8185.File.dat/ entiredoc_508.pdf (accessed May 12, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2007a. Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement: Surprise Field Office, Volumes I and II – May 2007. Cedarville, CA. http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/fo/surprise/propRMP-FEIS.html (accessed May 15, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2007b. Tuledad Allotment 2007 Annual Operating Plan. Cedarville, CA. [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2008. Record of Decision, Surprise Resource Management Plan: April 2008. Cedarville, CA. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/ blm/ca/pdf/surprise.Par.18713.File.dat/SurpriseROD2008.pdf (accessed May 15, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2011. Animal Unit Month (AUM). http://www.blm.gov/ nv/st/en/prog/grazing/animal_unit_months.html (accessed March 23, 2011).

Bleich, Vernon C., John D. Wehausen, Karen R. Jones, and Richard A. Weaver. 1990. Status of bighorn sheep in California, 1989 and translocations from 1971 through 1989. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 34th Annual Meeting, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. April 4-6.

Dobel, Mike. 2012a. Regional Supervising Biologist (Western Region), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. October 3.

Epps, Clinton W., Vernon C. Bleich, John Wehausen, and Steven G. Torres. 2003. Status of bighorn sheep in California. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 47th Annual Meeting, St. George, UT. April 8-11.

Flores, Jr., Elias. 2012. Wildlife Biologist (Surprise District), Bureau of Land Management. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 28.

Meintzer, Kyle M. 2009. Bighorn sheep? In northeastern California? California Chapter, Wild Sheep Foundation. http://cawsf.org/project2.htm (accessed June 5, 2012).

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2006. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2005-2006 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/biggame.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2007. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2006-2007 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/Big%20Game%20 Status%20Book_06_07.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2008a. Bighorn Sheep Die-off in Hay’s Canyon: 2007/2008. N.p. http://www.ndow.org/wild/health/HaysCanyonDieOff2007.pdf (accessed December 18, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2008b. Bighorn Sheep Die-off in Hay’s Canyon Range. http://www.ndow.org/about/news/pr/031108_bh_die_off.shtm (accessed December 18, 2011).

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2008c. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2007-2008 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/08_BG_Status _Bk.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2009. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2008-2009 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http:// www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/09_bg_status_bk. pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2010. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2009-2010 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/10_bg_status.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2011. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2010-2011 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/2011_bg_status.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012) [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2013. Nevada Department of Wildlife Big Game Restoration Program: 2012-2013. N.p. http://www.ndow.org/uploadedFiles/ndoworg/ Content/Wildlife_Education/Publications/Bighorn-Capture-Release-Program-News-2012-2013-R.pdf (accessed March 3, 2015). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Division of Wildlife (NDOW). 2001. Nevada Division of Wildlife’s Bighorn Sheep Management Plan: October 2001. Reno. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/plans/bighorn_ management_plan.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Soletti, Scott. 2012. Wildlife Biologist (Surprise District), Bureau of Land Management. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 23.

Surian, Steve. 2012. Supervisory Rangeland Management Specialist (Surprise District), Bureau of Land Management. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 11.

Tanner, Gregg. 2012a. Retired Game Bureau Chief (Statewide), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. October 31.

Tanner, Gregg. 2012b. Retired Game Bureau Chief (Statewide), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. November 5.

Western Hunter. 2000. Bighorns in Warner Mountains? J & D Outdoor Communications. http://www.westernhunter.com/Pages/Vol02Issue26/bighorns.html (accessed May 31, 2012).