MAJOR POLICIES

Introduction

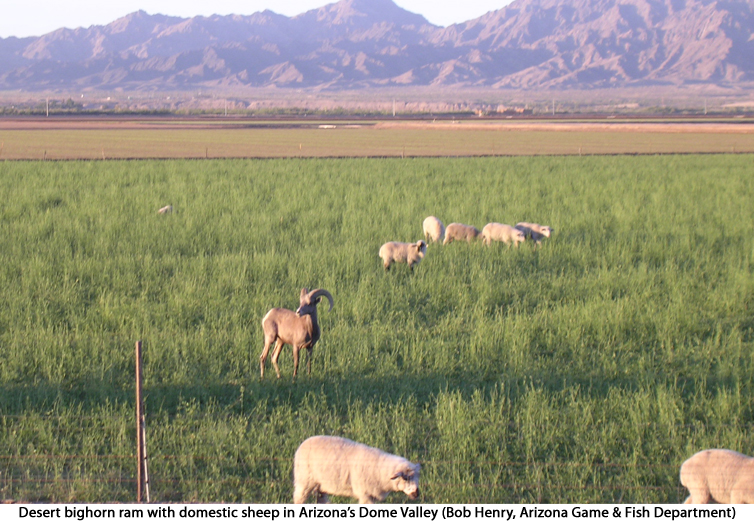

Managing wild-domestic sheep interaction can be difficult. According to Heimer, “a bighorn manager must face the down and dirty work associated with negotiating, establishing, and maintaining separation of bighorns from domestic sheep . . . . This is hard administrative work, and not a particularly preferred activity for field biologists or administrators in states with traditions of domestic sheep ranching” (2000, 133). With conflicts, emphasis is placed on managing domestic sheep because: “There is virtually no practical way to control movements of young bighorns, but control of domestic sheep is possible” (DBC Technical Staff 1990, 34).

The major bighorn-domestic sheep interaction management policies relate to keeping bighorns and domestic sheep separate. The U.S. Forest Service (USFS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and various state wildlife management agencies have their own policies for wild-domestic sheep interaction. Depending on circumstances, different agencies may or may not implement the policies described below. Wildlife managers’ policies largely relate to addressing distribution and movement of bighorns. Land managers’ policies primarily relate to regulating domestic sheep grazing on public lands (WAFWA 2010). Bighorn-domestic sheep separation policies are often attached to federal grazing permits or included in land management plans (USFS 2010).

Tim Schommer provides insights on separation practices based on his personal experience as a biologist with the USFS:

“Each allotment includes grazing practices specific to the allotment and permittee and each allotment carries its own set of unique circumstances that need to be evaluated. What works in one location may not work in another. The following factors affect the success or failure of a grazing practice: topography, bighorn sheep source habitat connectivity, bighorn sheep population size, proximity of domestic sheep grazing allotments to bighorn sheep populations, timing of allotment use, density of vegetation, and escape terrain. None of the [practices] can be determined effective without an active monitoring effort to detect the presence or absence of bighorn sheep near domestic sheep bands” (USFS 2010, 1).

The 1990 guidelines that the Desert Bighorn Council (DBC) composed for the BLM cover four key separation recommendations (buffer zones, livestock supervision, trailing restrictions, and prohibition of bighorn reintroduction to sites hosting domestic sheep) (DBC Technical Staff 1990). In 1992, the DBC’s guidelines became BLM advisory policy. In 1995, they became required policy for field offices. And, in 1998, the BLM revisited and renewed the guidelines (Brigham, Rominger, and Espinosa T. 2007). As discussed below, additional guidelines/policies are common in the U.S.

Buffer Zones

Buffer zones are one of the most effective ways separation can be accomplished (DBC Technical Staff 1990). The DBC’s technical staff states that: “No domestic sheep grazing should be authorized or allowed within buffer strips ≥13.5 km (8.4 mi) wide surrounding desert bighorn habitat, except where topographic features or other barriers prevent any interaction” (1990, 34). Aside from considering the problem of wandering young rams, the DBC’s technical staff justifies this recommendation by stating: “Bighorn and domestic sheep separation distances cited in the literature range from 3.2 to 32 km [(2 to 20 mi)]” (1990, 34). Bighorn reintroduction recommendations from 2001 indicate the necessity of a 23 km (14 mi) buffer (Shannon et al. 2008).

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) states: “Each situation is different and managers must design adequate buffers to prevent contact between bighorns and domestic sheep” (2003, 60). In Oregon, an 8-km (5-mi) buffer in spring and a 32-km (20-mi) buffer in fall have been sufficient to protect a population of California bighorns (ODFW 2003). Furthermore, Idaho’s 2010 bighorn management plan makes extensive use of digitally modeled buffers to predict wild sheep habitat (IDFG 2010).

Livestock Supervision

Livestock supervision is another DBC recommendation (DBC Technical Staff 1990). The DBC states that: “Domestic sheep that are trailed or grazed outside the 13.5-km [(8.4 mi)] buffer, but in the vicinity of desert bighorn ranges, should be closely supervised by competent, capable, and informed herders” (1990, 34). Communication can be an important component of effective supervision. Schommer notes that:

“Some operators are now equipping their herders with cell or satellite phones so they can immediately call authorities when bighorn sheep are observed in or close to domestic sheep. Authorities can either shoot, remove, or haze bighorn sheep. These practices can be helpful in preventing contact. However, some operators do not report to authorities when bighorn sheep are near their domestic sheep” (USFS 2010, 2).

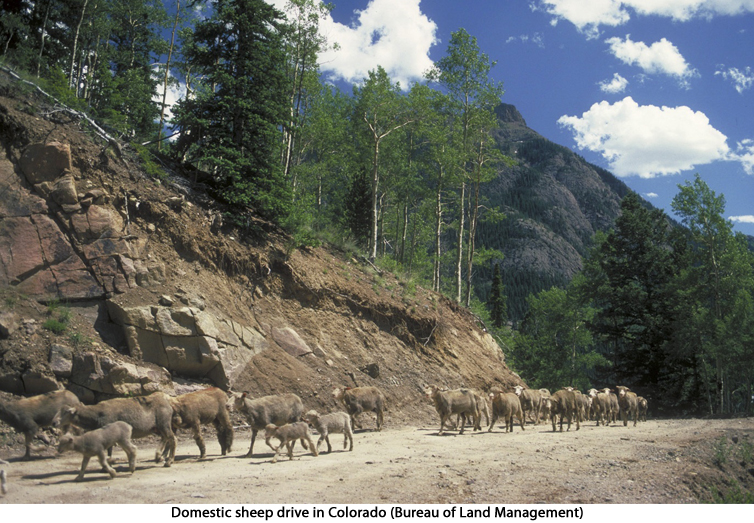

Trailing Restrictions

A third recommendation from the DBC relates to restricting trailing, which is the herding of domestic sheep from one allotment to another. The DBC states that: “Domestic sheep should be trucked rather than trailed, when trailing would bring sheep closer than 13.5 km [(8.4 mi)] to bighorn range. Trailing should never occur when domestic ewes are in estrus” (1990, 35). Rationale for this recommendation comes from the fact that: “When domestic ewes are in estrus, they will attract bighorn rams from distances >3.2 km [2 mi]” (DBC Technical Staff 1990, 35).

Schommer provides insights on this policy: “Trucking of domestic sheep instead of trailing has been effective in reducing strays. Strays increase the probability of contact with a bighorn sheep. However, because of cost and the potential for domestic sheep disease associated with this practice, most operators prefer to not truck their sheep” (USDA 2010, 2).

Prohibition of Reintroduction to Sites Hosting Domestic Sheep

A fourth DBC recommendation covers reintroduction. The DBC suggests that: “Bighorn sheep should not be reintroduced into areas where domestic sheep have grazed during the previous 4 years” (1990, 35). The DBC justifies this guideline by stating: “Two diseases that could be transmitted to bighorn after domestic sheep have been removed are footrot and soremouth. Both of these diseases can lie in the soil and, when conditions are right, be transmitted to bighorns. The soremouth virus can remain viable in the soil for 10 to 20 years” (1990, 34).

Agencies have followed the principles of the DBC’s reintroduction recommendation. In many areas, the presence of domestic sheep has prevented wildlife managers from establishing new bighorn populations in vacant, former range. Some states perform habitat evaluations that consider domestic sheep in potential transplant sites. For example, in 1993, the BLM and the California Department of Fish and Game decided not to reintroduce bighorns to northeastern California’s Amadee/Skedaddle Mountains partly because of concerns with domestic sheep (Torres, Bleich, and Wehausen 1994).

Domestic sheep issues have also prevented the augmentation of a bighorn population in Utah’s Leppy Hills (Shannon et al. 2008). Additionally, regarding a potential Arizona reintroduction site, Wakeling states: “The Chevelon Canyon area has remained a high priority for future releases, although a domestic sheep allotment in close proximity has kept this transplant from becoming a reality” (2007, 53). Furthermore, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) does not reintroduce California bighorns “to areas where they may come in contact with domestic or exotic sheep” (ODFW 2003, 19). Likewise, by 1999, the Nevada Division of Wildlife had commission policy that prevented them from transplanting bighorns to regions with active domestic sheep permits (Arthur et al. 1999).

Not all states have been sufficiently cautious regarding prohibiting reintroductions to sites with domestic sheep or goats. For example, through transplants in 1996, 1997, and 2000, the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP) reintroduced bighorns to a portion of the Elkhorn Mountains that contained domestic sheep. In 2008, after interacting with domestic sheep, over 90% of this population of about 230 bighorns died during a pneumonia outbreak (Byron 2008; MFWP 2010).

In a newspaper article, Byron describes MFWP biologist Tom Carlsen’s comments on the die-off:

“Carlsen noted that the bighorns were transplanted at least six miles away from the rancher’s grazing site, but that the younger rams apparently roamed farther during the rut than biologists anticipated” (2008). According to Carlsen: “Over time, as the herd numbers increased, they wandered closer to the domestic sheep, which surprised us because it wasn’t their kind of habitat” (Byron 2008).

Despite the carelessness illustrated by transplants in the Elkhorn Mountains, Montana’s 2010 bighorn management plan thoroughly addresses and acknowledges the domestic sheep disease problem (MFWP 2010). Just before the transplants, the state also had a 1995 bighorn transplant policy that “gives preference to sites that are not in close proximity to domestic sheep. . .” (MFWP 2010, 29).

Buying Out and Converting Grazing Allotments

Another common policy regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction is to buy out grazing allotments or convert sheep allotments to cattle. Heimer states:

“The most successful approach to reclaiming bighorn habitats from domestic sheep involves negotiating and funding retirement of domestic sheep grazing allotments on bighorn ranges . . . . Cooperation between federal agencies, most notably the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, FNAWS [(Foundation for North American Wild Sheep; now the Wild Sheep Foundation)], state wildlife management agencies, and progressive ranchers has produced significant progress in this area” (2000, 133).

Utah took the lead with this practice in the 1990s (Hurley et al. 1999). For example, in reference to Utah’s Bighorn Mountain bighorn population, Shannon et al. say: “Disease has had little influence on this herd, partially because several domestic sheep allotments were purchased in the early 1990s, and the BLM closed several others during this time” (2008, 185). As of 2008, the Utah chapter of the Wild Sheep Foundation “spent nearly $1,000,000 purchasing or converting domestic sheep allotments to cattle allotments” (Shannon et al. 2008, 188).

In Oregon, “biologists work with land managers and permittees to modify grazing allotments or change class of livestock grazed from sheep to cattle” (ODFW 2003, 8). Wild sheep advocacy groups’ purchase of a grazing allotment in Oregon’s Wallowa Mountains retired the last domestic sheep grazing allotment in that region. The ODFW has also converted most domestic sheep allotments in California bighorn reintroduction areas to cattle before transplanting wild sheep (ODFW 2003).

By 1999, Wyoming had recently completed its first allotment buyout (Hurley et al. 1999). According to Meyer, in 1999, Idaho was also “working on buying out sheep allotments on both Forest Service and BLM lands so [the state could] transplant [bighorn] sheep” (Hurley et al. 1999, 284).

According to Ellenberger: “[In Colorado,] we are beginning cooperative management of domestic sheep allotments in proximity to bighorn herds. This project is in the early stages and will probably face some opposition from land management agencies as well as livestock operators” (Arthur et al. 1999, 397). While buyouts and conversions are effective ways to reduce the threat of domestic sheep on public land, conservation easements restricting domestic sheep on private land are another option (Toweill and Geist 1999).

Education and Negotiation

Another important policy regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction is the implementation of education and negotiation with woolgrowers and other stakeholders. While education/negotiation is a major factor in acquiring allotment buyouts and conversions, it also applies to other situations, like noncommercial domestic sheep. For example, when ODFW biologist Craig Foster knows of a farm flock of domestic sheep or hobby animals that could threaten bighorns, he has personally visited with landowners and given them literature (Hurley et al. 1999). Educating the public about bighorn disease risk is a priority in Oregon. According to the ODFW: “Videos and brochures are used to educate the public on the dangers . . . domestic sheep and goats pose to bighorns” (2003, 8).

In both Oregon and Idaho, wildlife managers have used a brochure (sponsored by the Wild Sheep Foundation) on bighorn-domestic sheep interaction to educate stakeholders (Hurley et al. 1999). Regarding Colorado, Ellenberger states: “We need to work with land management agencies, livestock organizations and the general public to make them aware of the need to keep bighorn sheep and domestic sheep segregated to decrease the potential for transmission of disease” (Arthur et al. 1999, 398).

Removing Wandering Bighorns

According to Mack: “Removing (placing in captivity or killing) bighorn sheep known or suspected to have contacted domestic sheep or goats is a common management practice among western U.S. states, and is commonly referred to as the ‘wandering wild sheep policy’” (2008, 211). This policy was implemented in northeastern California’s Warner Mountains when a young ram was killed after he was seen with a group of domestic sheep (Meintzer 2009; Epps et al. 2003). More recently (in November 2011), Idaho Department of Fish and Game officials shot a bighorn ram after it was observed near domestic sheep close to Castleford (Times-News 2011). All western states hosting bighorns (except for Texas) endorse the “wandering wild sheep policy.” One reason Texas doesn’t use the policy is because it is not applicable there due to a lack of bighorn-domestic sheep disease concerns (Mack 2008).

Oregon has “extended authority to the public to remove the animal, but this authority is seldom used” (Erickson, Coggins, and Alt 2000, 87). According to Foster: “If they [(landowners)] see one of my wild bighorns near their domestic sheep, I want it dead. Shoot the bighorn before it goes home” (Hurley et al. 1999, 284). Foster goes on to say that he wants landowners to call him first, but they should shoot a stray bighorn if they are unable to contact him (Hurley et al. 1999). He remarks: “We don’t have a lot of open range issues. I guess our agency’s feeling is we’d rather have one dead bighorn than take the risk of an all-age die-off” (Hurley et al. 1999, 284).

Montana usually kills bighorns that have had known domestic sheep or goat contact, but the lethal removal policy is written protocol in only one of the state’s seven administrative regions (MFWP 2010). Mack criticizes the efficacy of the “wandering wild sheep” policy and indicates that sometimes “the need to remove bighorn sheep because of interactions with domestic sheep or goats should be viewed as a management failure triggering implementation of more effective separation strategies to prevent contact and preclude the need for further removal of wild sheep” (2008, 215).

Efficacy

Schommer states that: “Agreeing to [policies] on paper is easier; implementing them on the ground for the entire grazing season year after year is more difficult. Many examples of [practices] not always being implemented on the ground exist. And [practices] can only be effective if fully implemented and readily adapted if not working” (USFS 2010, 3). Schommer notes: “Based on my experience, the only significant reduction in risk of contact that I have witnessed is when [practices] are implemented in open, gentle, non-bighorn sheep habitat where domestic sheep can be easily controlled and monitored, and a large buffer exists between the two species” (USFS 2010, 3). The rugged nature of bighorn habitat increases the difficulty of effective separation policy implementation (USFS 2010). Schommer concludes by emphasizing that separation policies are site-specific and only effective in limited situations (USFS 2010). He also provides an example of why efficacy can be elusive.

“On the Temperance Creek Allotment in Hells Canyon in the 1980s and early 1990s, domestic and bighorn sheep were separated by over 20 air miles and almost all of the [best management practices] described above [in Schommer’s analysis] were implemented. Despite these grazing practices and large separation distances, the two species could not be kept apart. Detecting bighorn and domestic sheep in this open, rocky, continuous bighorn sheep habitat was very difficult. Known mixing of the two species approximately every other year resulted in large catastrophic bighorn sheep die-offs” (USFS 2010, 3-4)

Conclusion

The policies and trends addressed above are some of the major ones that stand out. However, regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction, there are numerous ideas/policies (e.g., double fencing, risk assessments with cartographic comparisons of wild and domestic sheep distributions, inclusion of a wild-domestic sheep interaction notification requirement in grazing allotment instructions, etc.). The Wild Sheep Working Group (WSWG) of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies provides many more examples (WAFWA 2010). In 2007, the WSWG released its initial “Recommendations for Domestic Sheep and Goat Management in Wild Sheep Habitat” (WAFWA 2007). In 2010, the WSWG released an updated version of these recommendations. That 2010 report is one of the most comprehensive, up-to-date documents focusing solely on bighorn-domestic sheep interaction management (WAFWA 2010). In 2012, the WAFWA released a more user-friendly version of this document (with photos and maps) aimed at the public (WAFWA 2012). Schommer’s evaluation of separation practices is also especially informative (USFS 2010).

REFERENCES

Arthur, Steven M., Ian Hatter, Alasdair Veitch, John Nagy, Jean Carey, Jon T. Jorgenson, Raymond Lee, John Ellenberger, John Beecham, John J. McCarthy, Gary Schlichtemeier, Larry T. Gilbertson, Bill Dunn, Don Whittaker, Ted A. Benzon, Jim Karpowitz, George Tsukamato, Kevin Hurley, Steven G. Torres, Craig Mortimore, Mike Oehler, Patrick Cummings, Craig Stevenson, Eric Rominger, and Doug Humphreys. 1999. Appendix A: Wild sheep status questionnaires. In proceedings of 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference, Reno, NV. April 6-9.

Brigham, William R., Eric M. Rominger, and Alejandro Espinosa T. 2007. Desert bighorn sheep management: Reflecting on the past and hoping for the future. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 49th Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV. April 3-6.

Byron, Eve. 2008. Die-off decimates bighorn sheep herd. Helena Independent Record. April 11. http://www.wildsheepfoundation.org/Page.php/News/36/1207026000-1209528000 (accessed December 25, 2011).

Desert Bighorn Council (DBC) Technical Staff. 1990. Guidelines for the management of domestic sheep in the vicinity of desert bighorn habitat. In transactions of DBC’s 34th Annual Meeting, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. April 4-6.

Epps, Clinton W., Vernon C. Bleich, John Wehausen, and Steven G. Torres. 2003. Status of bighorn sheep in California. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 47th Annual Meeting, St. George, UT. April 8-11.

Erickson, Glenn L. (moderator and panel member), Vic Coggins, and Kurt Alt (panel members). 2000. Designing a protocol: What should you do if you are faced with a bighorn sheep die-off? Working session in proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 12th Biennial Symposium, Whitehorse, YK. May 31-June 4.

Heimer, Wayne E. 2000. The Foundation for North American Wild Sheep – A sheep biologist’s view from the inside. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 12th Biennial Symposium, Whitehorse, YK. May 31-June 4.

Hurley, Kevin (moderator), Jon Jorgenson, Helen Schwantje, Craig Foster, Herb Meyer, Amy Fisher, Dave Hacker, Harley Metz, Jim Karpowitz, Melanie Woolever, Dick Weaver, Tim Schommer, Cal McCluskey, Duncan Gilchrist, Jim Bailey, Bonnie Pritchard, Dave Byington, Dave Smith, Bill Foreyt, and Dave Hunter (discussion members). 1999. Open discussion – Are we effectively reducing interaction between domestic and wild sheep? Discussion in proceedings of 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference, Reno, NV. April 6-9.

Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG). 2010. Idaho Bighorn Sheep Management Plan: 2010. Boise. http://fishandgame.idaho.gov/public/wildlife/planBighorn.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Meintzer, Kyle M. 2009. Bighorn sheep? In northeastern California? California Chapter, Wild Sheep Foundation. http://cawsf.org/project2.htm (accessed June 5, 2012).

Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP). 2010. Montana Bighorn Sheep Conservation Strategy: 2010. Helena. http://fwpiis.mt.gov/content/getItem.aspx?id =397 46 (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW). 2003. Oregon’s Bighorn Sheep & Rocky Mountain Goat Management Plan: December 2003. Salem. http://www.dfw.state.or.us/ wildlife/management_plans/docs/sgplan_1203.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Shannon, Justin M., Daniel D. Olson, Jericho C. Whiting, Jerran T. Flinders, and Tom S. Smith. 2008. Status, distribution, and history of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep in Utah. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 16th Biennial Symposium, Midway, UT. April 27-May 1.

Times-News. 2011. Fish and Game kills ram near Castleford. Times-News. November 10. http://m.magicvalley.com/news/local/fish-and-game-kills-ram-near-castleford/article_ a42ac29c-0bca-11e1-bdcf-001cc4c03286.html (accessed November 11, 2012).

Torres, Steven G., Vernon C. Bleich, and John D. Wehausen. 1994. Status of bighorn sheep in California, 1993. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 38th Annual Meeting, Moab, UT. April 6-8.

Toweill, Dale E., and Valerius Geist. 1999. Return of royalty: Wild sheep of North America. Missoula, MT: Boone and Crockett Club and Foundation for North American Wild Sheep.

U.S. Forest Service. 2010. Appendix F: Best Management Practices Report, by Tim Schommer. In Southwest Idaho Ecogroup Land and Resource Management Plans – Update to the Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement – Boise National Forest, Payette National Forest, Sawtooth National Forest. McCall, ID. http://www.fs.usda.gov/ Internet/FSE_ DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5139347.pdf (accessed May 11, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Wakeling, Brian F. 2007. Status of bighorn sheep in Arizona, 2006-2007. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 49th Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV. April 3-6.

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA). 2007. WAFWA Wild Sheep Working Group Initial Subcommittee Recommendations for Domestic Sheep and Goat Management In Wild Sheep Habitat (June 21, 2007). N.p.: WAFWA. Web address no longer available (accessed on April 23, 2009; based on file info).

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. 2010. WAFWA Wild Sheep Working Group recommendations for domestic sheep and goat management in wild sheep habitat: July 21, 2010. N.p.: WAFWA. http://www.wafwa.org/documents/wswg/WSWGManagement ofDomesticSheepandGoatsinWildSheepHabitatReport.pdf (accessed May 17, 2012).

Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. 2012. Recommendations for Domestic Sheep and Goat Management in Wild Sheep Habitat. N.p.: WAFWA. http://www.wafwa.org /documents/wswg/RecommendationsFor DomesticSheepGoatManagement.pdf (accessed July 11, 2012).