Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains, CO: 1997-2000

INTRODUCTION

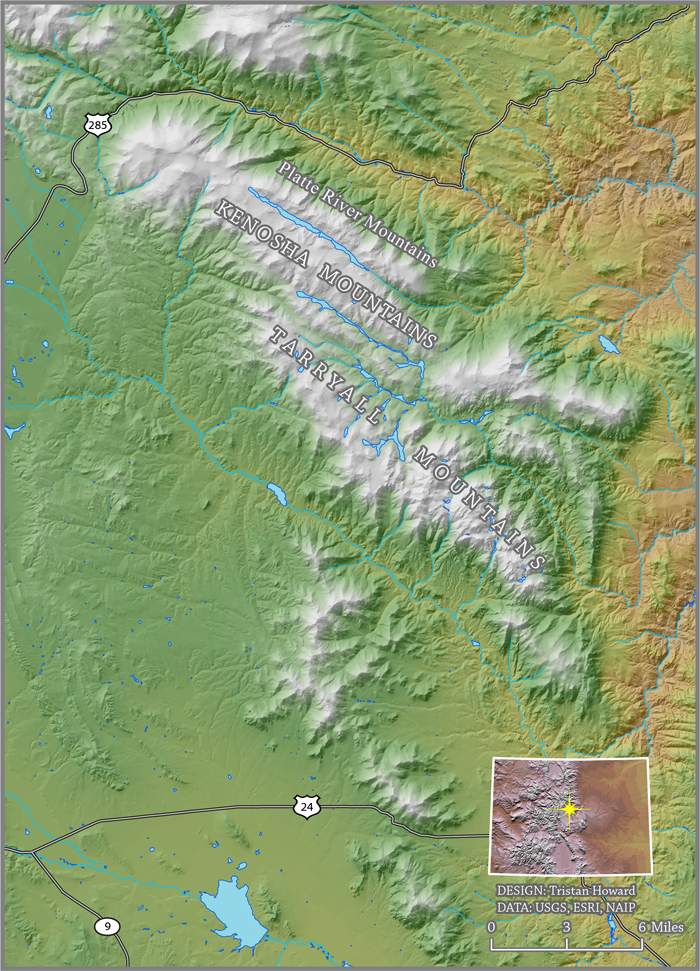

The Tarryall Mountains (39° 13’ 54.41”N, 105° 31’ 43.15”W) and Kenosha Mountains (39° 21’ 55.06”N, 105° 36’ 21.32”W) are connected mountain ranges in central Colorado’s Park County. They are located about 64 km (40 mi) southwest of Denver (George et al. 2008; Google Earth 2012). These mountains primarily lie in the Pike National Forest (Google Earth 2012). According to the Colorado Division of Wildlife (CDOW), the Tarryall/Kenosha “bighorn population is composed of three relatively discrete herds with separate winter ranges (Kenosha Mountains, Sugarloaf Mountain, and Twin Eagles). Within this population, there is little interchange of ewes among herds but considerable commingling and exchange of rams” (2009, 12). Because of the interchange, the Tarryall and Kenosha bighorns are managed as a single population (USFS 2007).

In a pre-outbreak 1990s study, George et al. described the range of Tarryall/Kenosha bighorns by dividing their habitat into two main subunits:

“The Kenosha Mountains . . . subunit was approximately 65 km2 and contained 1 subpopulation that ranged in the Kenosha and Platte River Mountains, and N. Tarryall Peak area. Elevation ranged from 2,800-3,800 m [9,186-12,467 ft]. Bighorns were primarily found on alpine tundra and on mixed grass slopes interspersed with bristlecone pine (Pinus aristata), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), Englemann spruce (Picea englemannii), aspen (Populus tremuloides) and rock outcrops. Willows (Salix spp.) and large stands of conifers were used occasionally. Escape cover consisted of rock outcrops that seldom exceeded 100 m [328 ft] in vertical relief.

The Tarryall Mountains . . . subunit, was approximately 130 km2, abutted the southeastern boundary of the [Kenosha Mountains subunit], and contained 2 bighorn subpopulations [Sugarloaf Mountain and Twin Eagles]. Topographic relief was greater than in the [Kenosha Mountains subunit], with cliffs and rock outcrops often exceeding 200 m [656 ft] in vertical relief. Elevation ranged from 2,400-3,800 m [7,874-12,467 ft]. During March and April most bighorn used mixed grass slopes interspersed with Ponderosa pine and aspen, and riparian meadows along Tarryall Creek. Bighorn also used steep, broken slopes with conifer cover approaching 50%. Alpine tundra and dense stands of Douglas fir and Englemann spruce received little use in winter and spring” (1996, 21).

Bighorns in the Tarryall Mountains congregated at lower elevations along Tarryall Creek in winter with the Twin Eagles herd wintering about 15 km (9 mi) downstream of the Sugarloaf herd (George et al. 2008). George et al. add that Kenosha bighorns “occasionally congregated in subalpine habitats in late winter or spring in Black Canyon and Long Gulch. [Their] range was separated from the other two herds by at least 10 km (6 mi) during all seasons” (2008, 390-391).

The Rocky Mountain bighorn population in the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains is native, so no reintroduction was necessary to establish wild sheep there (Toweill and Geist 1999). A domestic sheep (that likely originated from private lands) was observed with Tarryall/Kenosha bighorns during their 1997-2000 pneumonia outbreak (George et al. 2008; USFS 2007). That outbreak reduced both overall bighorn numbers and subsequent lamb recruitment rates (George et al. 2008; USFS 2007). No policy documents were discovered that both covered wild-domestic sheep interaction in the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains and would have been applicable at the time of the area’s outbreak.

The policy analysis criteria addressing buffers, sheepherder supervision rules, trailing restrictions, consideration of domestic presence before reintroduction, and grazing alteration efforts are not applicable to the Tarrryall and Kenosha Mountains because no public land domestic sheep allotments existed in the area, and the ranges’ bighorns were native (George 2012; USFS 2007; Toweill and Geist 1999). Some education of local domestic sheep owners occurred because of the Tarryall/Kenosha outbreak. Bighorns near domestic sheep in the area were not removed from the wild. Regarding management of the Tarryall/Kenosha wild-domestic sheep issue, coordination existed, tension was unlikely, and there were no funding difficulties (George 2012). Before analyzing specific interaction policies, it helps to first have background information on the history of bighorns in the Tarryall and Kenosha Mountains.

BIGHORN POPULATION HISTORY PRIOR TO OUTBREAK

Unlike the other bighorn populations profiled in this study, wild sheep composing the Tarryall/Kenosha population were not reintroduced. They were native to their range before, during, and after Euro-American settlement (Toweill and Geist 1999). The CDOW provides a summary of this population’s earlier struggles with disease:

“In the late 1800s, die-offs were reported in bighorn sheep in the Tarryall Mountains . . . . In 1953, the state’s largest bighorn population residing in the Tarryall and Kenosha Mountains experienced a die-off caused by pneumonia that reduced the population from an estimated 1,000 animals (some observers have said 2,000) to 30 within two years; the Tarryall-Kenosha epidemic likely extended from a 1952 outbreak on Pikes Peak. The causes of these early die-offs are hard to verify retrospectively, but contact with domestic livestock that led to the introduction of exotic diseases and parasites seems the most logical explanation” (CDOW 2009, 1).

This die-off was among Colorado’s first well-documented wild sheep epizootics that affected all ages of bighorns. In 1996, about 375 bighorns lived in the Tarryall/Kenosha population (CDOW 2009). A portion of this bighorn population’s habitat was only about 14 km (8.7 mi) from fenced domestic sheep (George 2012).

NEARBY DOMESTIC SHEEP

On December 18, 1997 (after the beginning of the Tarryall/Kenosha outbreak and the discovery of nine wild sheep carcasses), a field technician was tracking bighorns on Sugarloaf Mountain when he saw a domestic sheep ram. George et al. describe what happened next:

“When first observed, the domestic sheep appeared to be following the technician. However, when the technician tried to approach the domestic sheep it fled and joined a nearby group of bighorn sheep. According to his notes, “Several attempts were made by the bighorns to keep the domestic male away but it was persistent and eventually allowed to graze with them.” (T. Verry, unpubl. field notes, CDOW and United States Forest Service). We made unsuccessful attempts to capture the domestic sheep and to locate its owner later that day and again on the morning of 19 December. We subsequently shot the domestic sheep on 19 December while it was still associated with a group of bighorn sheep . . . . The carcass of the domestic sheep was transported to CSUDL for necropsy. This was the first (and only) time during our 10-yr study that a domestic sheep was found with bighorn sheep on range in the study area” (2008, 393).

George et al. add that “given the domestic sheep’s recalcitrance and the difficulty of observing it against the snow pack, we believe this animal may have been present somewhere on the Sugarloaf Mountain winter range for several weeks prior to being detected” (2008, 398). According to the USFS, regarding the Tarryall/Kenosha bighorn population: “There is no history of domestic sheep and goat allotments on public lands within the herd units, pointing to hobby flocks on private land as the probable source of exposure to pneumonia. Disease is likely to be a significant, chronic threat to this herd” (USFS 2007, 43).

Colorado Parks and Wildlife (new name for CDOW) biologist Janet George notes that “the domestic sheep appeared from an unknown source and no owner was ever identified” (2012). George adds that:

“. . . a small, fenced private collection of domestic sheep/goats was identified about 14 km [8.7 mi] from where the outbreak started . . . . The origin of the stray domestic ram associated with the disease outbreak remains unknown and there is no evidence it came from the small private collection” (2012).

While its origins may be uncertain, a domestic sheep was the likely source of a major bighorn pneumonia outbreak in the Tarryall and Kenosha Mountains.

OUTBREAK SUMMARY

From 1997-2000, bighorns inhabiting the Tarryall and Kenosha Mountains experienced a pneumonia outbreak that reduced bighorn numbers and subsequent lamb recruitment (George et al. 2008). According to George et al.: “The onset of this epidemic coincided temporally and spatially with the appearance of a single domestic sheep . . . on the Sugarloaf Mountain herd’s winter range in December 1997” (2008, 388).

On December 2, a dead radiocollared bighorn ewe was discovered on Sugarloaf Mountain. A necropsy performed the next day diagnosed the ewe with pneumonia. From December 8-19, eight more bighorn carcasses were found—all within about one km (0.6 mi) of the discovery location of the original dead ewe. Two of these carcasses were found to be infected with pneumonia (George et al. 2008).

Soon after the outbreak started, CDOW took action. Agency staff knew local bighorn movement patterns and predicted that bighorn rams from the Sugarloaf Mountain herd would spread the disease when they dispersed in late winter and summer. So, wildlife managers vaccinated seven bighorns in the Sugarloaf Mountain herd and a combined total of 39 bighorns in the nearby Twin Eagles and Kenosha Mountains subpopulations. Managers administered vaccinations via hand injections, projectile syringes, and biobullets (George et al. 2008). The summary of George et al. adds:

“Although only bighorns in the Sugarloaf Mountain herd were affected in 1997–98, cases also occurred during 1998–99 in the other two wintering herds, likely after the epidemic spread via established seasonal movements of male bighorns. In all, we located 86 bighorn carcasses during 1997–2000. Three species of Pasteurella were isolated in various combinations from affected lung tissues from 20 bighorn carcasses where tissues were available and suitable for diagnostic evaluation; with one exception, b-hemolytic Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica . . . was isolated from lung tissues of cases evaluated during winter 1997–98” (2008, 388).

The 1997-2000 Tarryall/Kenosha disease outbreak directly killed at least 72 bighorns—approximately 28 percent of the estimated population. Vaccination of bighorns and removal of the nearby domestic sheep did not prevent substantial mortality or improve later lamb recruitment (George et al. 2008). George et al. remark that “the resulting depression in the . . . bighorn population’s survival, recruitment, and size followed the appearance of a single domestic sheep on native bighorn winter range and occurred in the absence of other known or suspected inciting factors, illustrating the potential consequences of contact between these species under natural conditions” (2008, 395-396).

According to the USFS, “lamb:ewe ratios fell from pre-epizootic levels of 40 to 50:100 to a post-epizootic level of 0:100, and they have only increased to about 25:100 since 2002” (2007, 43). Post-hunt estimates indicate about 110 bighorns lived in the Tarryall/Kenosha population in 2012 (CDOW 2012). These bighorns are a long way from recovering to their 1996 pre-outbreak population level of about 375 animals (CDOW 2009). An analysis of policy documents was undertaken in an effort to gain insights on why wildlife managers failed to prevent the Tarryall/Kenosha bighorn population from reaching such a precarious, suppressed position.

POLICY DOCUMENTS

Colorado’s 2009 bighorn management plan devotes much attention to the wild-domestic sheep disease problem. It even has a section dedicated to “Bighorn Sheep-Domestic Livestock Disease Interactions.” However, the plan lists current and aspirational strategies and goals without specifically referencing older interaction policies that were in place from 1997-2000 (CDOW 2009).

The 1984 land and resource management plan for the Pike and San Isabel National Forests covers the range of the Tarryall/Kenosha bighorns and was in place at the time of the outbreak (USFS 1984). The plan mentions domestic sheep grazing allotments, but according to the USFS, there were no sheep allotments within Tarryall/Kenosha bighorn range (USFS 1984, 2007). The Pike and San Isabel National Forests only had four permitted domestic sheep bands in 1984. The Pike/San Isabel plan lists bighorns as a management indicator species, but it does not address any specific policies regarding wild-domestic sheep separation (USFS 1984). An inquiry to the Pike National Forest revealed that no USFS bighorn-domestic sheep interaction policies were in place in the Tarryall/Kenosha region from 1997-2000 (Meyer 2012).

Now that exposition has been offered on the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains bighorn die-off and elements related to it, one is better equipped to analyze specific wild-domestic sheep interaction policies.

POLICY ANALYSIS CRITERIA

1.) Were clearly defined buffer zones established to ensure separation of bighorns and domestic sheep?

Answer and Explanation

Wild-domestic sheep separation buffer zones were not in place on Tarryall/Kenosha bighorn range (George 2012). According to George: “There were no known domestic sheep within or nearby the range of the Tarryall-Kenosha Mountains bighorn range so no need for a buffer” (2012).

2.) Were special supervision rules in place for sheepherders?

Answer and Explanation

This criterion is not applicable because no public land domestic sheep or goat grazing allotments existed in the Tarryall or Kenosha Mountains during the disease outbreak (USFS 2007).

3.) Were domestic sheep trailing restrictions in place to ensure separation?

This criterion is not applicable because of the absence of domestic sheep grazing allotments in the Tarryall and Kenosha Mountains (USFS 2007).

4.) Were policies in place or was consideration taken regarding the concept of prohibiting bighorn reintroduction to the site if it hosted domestic sheep?

Answer and Explanation

This criterion is not applicable because bighorns in the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains were native and not reintroduced (Toweill and Geist 1999).

5.) Before the disease outbreak, was any effort made to buy out nearby domestic sheep grazing allotments or convert them to cattle?

Answer and Explanation

This criterion is not applicable because there were no local domestic sheep allotments to buy out (USFS 2007).

6.) Were other forms of negotiation and/or education attempted with local stakeholders regarding the issue of bighorn-domestic sheep disease transmission?

Answer and Implementation

Though it did not happen before the outbreak, agency-initiated education of at least one private landowner took place because of the Tarryall/Kenosha die-off. A small group of fenced domestic sheep and goats existed on private land about 14 km (8.7 mi) from the epizootic’s starting location (George 2012). According to George, after the outbreak: “Local field staff contacted the owner and explained the risk to bighorns” (2012).

7.) If wandering bighorns got too close to domestic sheep, were they ever removed from the wild in or near this location?

Answer and Explanation

No bighorns in the Tarryall or Kenosha Mountains were ever removed from the wild because of proximity to domestic sheep. George remarked: “No wandering bighorns associated with the Tarryall herd have been identified approaching domestic sheep” (2012).

8.) Did coordination and/or tension exist between different levels (federal, state, local) of government management agencies regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction?

Answer and Nature

Coordination existed at the state level. In the answers to a questionnaire presented to biologists at the 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference in 1999, John Ellenberger states: “In general, conflicts between state and federal agencies have been minimal. Preserving and maintaining sheep populations and their habitats is a high priority for all agencies in the state” (Arthur et al. 1999, 397). Ellenberger adds: “We are beginning cooperative management of domestic sheep allotments in proximity to bighorn herds. This project is in the early stages and will probably face some opposition from land management agencies as well as livestock operators” (Arthur et al. 1999, 397).

9.) Did you encounter funding difficulties regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction management?

Answer and Explanation

This criterion is not applicable because of the lack of knowledge of domestic sheep in Tarryall/Kenosaha bighorn range in the 1990s (George 2012). Regarding management before the die-off, George notes that there were no known “domestic sheep within the Tarryall bighorn range so no need for funding” (2012).

POLICY EFFICACY SUMMARY

The main policy trend that stands out for the Tarryall/Kenosha Mountains was that various wild-domestic sheep interaction policies were not applicable there. This is because of a lack of domestic sheep allotments in the area and the native status of the Tarryall/Kenosha bighorns (USFS 2007; Toweill and Geist 1999). The area lacked clear wild-domestic separation buffers, education occurred, and bighorns near domestic sheep were not removed from the wild (George 2012). These missing but applicable policies may have contributed to disease. Considering the fact that hobby animals were the main domestic sheep nearby (USFS 2007) and the mystery surrounding the lone domestic sheep that may have initiated the bighorn die-off (George et al. 2008), domestic sheep presence was probably not prominent enough for agencies to consider implementing the above policies. Education of a local sheep owner occurred, but it happened after the die-off (George 2012), which was too late for it to be effective.

REFERENCES

Arthur, Steven M., Ian Hatter, Alasdair Veitch, John Nagy, Jean Carey, Jon T. Jorgenson, Raymond Lee, John Ellenberger, John Beecham, John J. McCarthy, Gary Schlichtemeier, Larry T. Gilbertson, Bill Dunn, Don Whittaker, Ted A. Benzon, Jim Karpowitz, George Tsukamato, Kevin Hurley, Steven G. Torres, Craig Mortimore, Mike Oehler, Patrick Cummings, Craig Stevenson, Eric Rominger, and Doug Humphreys. 1999. Appendix A: Wild sheep status questionnaires. In proceedings of 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference, Reno, NV. April 6-9.

Colorado Division of Wildlife (CDOW). 2009. Colorado Bighorn Sheep Management Plan: 2009-2019. Edited by J.L. George, R. Kahn, M.W. Miller, and B. Watkins. Denver. http:// wildlife.state.co.us/SiteCollectionDocuments/DOW/WildlifeSpecies/Mammals/Colorado BighornSheepManagementPlan2009-2019.pdf (accessed October 15, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Colorado Division of Wildlife (CDOW). 2012. Colorado Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep 2012 Posthunt Population Estimates – Draft 12/15/2012. http://wildlife.state.co.us/Site CollectionDocuments/DOW/Hunting/BigGame/Statistics/RockyMountainBighornSheep/2012

RMBighornPopulationEstimate.pdf (accessed April 28, 2013).

Meyer, Kristen. 2012. Wildlife Biologist (Pike National Forest), U.S. Forest Service. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. June 13.

George, Janet L., Michael W. Miller, Gary C. White, and Jack Vayhinger. 1996. Comparison of mark-resight population size estimators for bighorn sheep in alpine and timbered habitats. In proceedings of Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council’s 10th Annual Symposium, Silverthorne, CO. April 29-May 3.

George, Janet L., Daniel J. Martin, Paul M. Lukacs, and Michael W. Miller. 2008. Epidemic Pasteurellosis in a bighorn sheep population coinciding with the appearance of a domestic sheep. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 44, no. 2 (April): 388-403.

George, Janet L. 2012. Senior Terrestrial Biologist (Northeast Region), Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by e-mail. July 16.

Toweill, Dale E., and Valerius Geist. 1999. Return of royalty: Wild sheep of North America. Missoula, MT: Boone and Crockett Club and Foundation for North American Wild Sheep.

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 1984. Land and Resource Management Plan: Pike and San Isabel National Forests; Comanche and Cimarron National Grasslands. Pueblo, CO. http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/psicc/landmanagement/planning (accessed June 6, 2012). [govt. doc.]

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 2007. Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis): A Technical Conservation Assessment, Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, February 12, 2007, by John J. Beecham, Cameron P. Collins, and Timothy D. Reynolds. Rigby, ID. http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/rockymountainbig hornsheep.pdf (accessed January 7, 2012). [govt. doc.]