Tobin Range, NV: 1991

INTRODUCTION

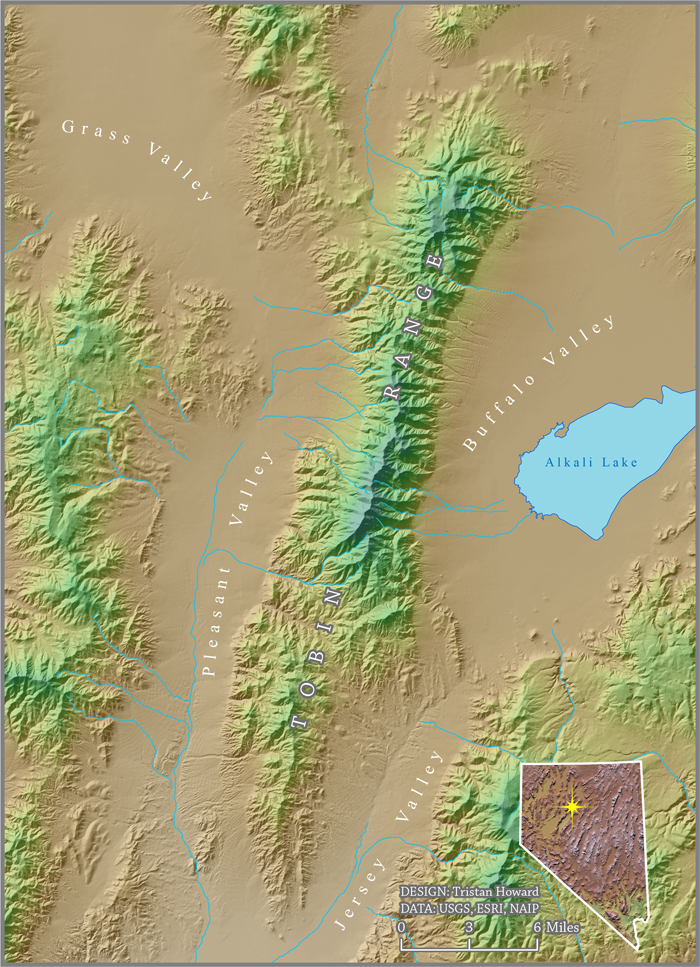

The Tobin Range (40° 26’ 1.36”N, 117° 29’ 50.94”W) is located in eastern Pershing County in north-central Nevada (Google Earth 2012; USFS 2012b). This fault-block mountain range is about 48 km (30 mi) southeast of Winnemucca (BLM 2012b; Google Earth 2012). According to the BLM’s 1995 mountain sheep ecosystem management strategy, about 97 percent of the Tobin Range bighorn habitat bioregion is BLM land, and 3 percent is private land (BLM 1995). The Tobin Range is part of the Tobin Range Wilderness Study Area (WSA) managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). This WSA includes “13,107 acres of public lands and surrounds 120 acres of private lands” (BLM 2012b, 1). Elevations within the WSA range from 1,414-2,979 m (4,640-9,775 ft). The BLM provides further details on the Tobin Range:

“The upper elevations (7,000-9,700 feet) are characterized by smooth, dominant ridges separated by shallow drainages. The foothill section has roughly parallel (east-west) deeply-cut drainages and several dominant rock outcrops and is bounded on the west by a prominent fault scarp 10 to 20 feet high, formed in 1915. This fault was exposed during a major earthquake. The lowest section, the fringing desert piedmont, is a gently sloping alluvial fan on the east side of Pleasant Valley, with several parallel, east-west drainages separated by low ridges” (2012b, 1).

In the Tobin Range, sagebrush (Artemisia spp.) is the main vegetation above 2,134 m (7,000 ft), and big sage (Artemisia tridentata Nutt.) dominates below 2,134 m (NDOW 2012a, b; NRCS 2012, 2002). Juniper trees (Juniperus) and small riparian areas also exist in the Tobin Range’s lower elevations (BLM 2012).

In 1984, desert bighorns were reintroduced to the Tobin Range (NDOW 2010). Domestic sheep roamed a nearby private ranch during the time of the Tobin Range disease outbreak, and bighorn-domestic sheep interaction was observed in the area prior to its disease event (Ward et al. 1997; Tanner 2012a). In the early 1990s, respiratory disease eliminated all Tobin Range bighorns (Cummings and Stevenson 1995). A variety of BLM documents (including a management framework plan, desert bighorn plan, and guidelines for managing domestic sheep in desert bighorn habitat) applied to the Tobin Range at the time of its bighorn die-off (BLM 1982, 1989, 1990). A Nevada Department of Fish and Game (NDFG) biological bulletin on the state’s desert bighorns was also relevant (NDFG 1978). In the 1980s-1990s, influential litigation transpired, which dealt with the threat domestic sheep posed to bighorns in the Tobin Range (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991).

Regarding wild-domestic sheep interaction policies, the Tobin Range lacked clear buffers, special sheepherder supervision rules, and trailing restrictions (Tanner 2012a). Nonetheless, domestic sheep presence was considered before reintroduction, grazing allotment alteration was implemented, and negotiation or education occurred (BLM 1982; DBC Technical Staff 1990; Jeffress 2012a; Tanner 2012a). Bighorns near domestic sheep were not removed from the area (Tanner 2012b). Agencies managing Tobin bighorns also coordinated their management activities and did not experience significant tension or funding difficulties (Tanner 2012a, b). For sufficient context on the Tobin Range’s wild-domestic sheep interaction policies, it helps to know the history of the area’s desert bighorns before respiratory disease triggered their demise.

BIGHORN POPULATION HISTORY PRIOR TO OUTBREAK

The Tobin desert bighorn population was established in 1984 when 34 bighorns from southern Nevada’s River Mountains were released into Miller Basin (NDOW 2010; Google Earth 2012). In October 1991, wildlife managers transplanted 18 additional bighorns from the Black Mountains near Lake Mead to Indian Canyon in an effort to augment the Tobin population (Ward et al. 1997; NDOW 2010). Just how large did the Tobin population get right before it experienced disease? That is unknown. According to Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW) Regional Supervising Biologist Mike Dobel: “I have no records of population estimates during this time frame as it was an un-hunted population which did not require published estimates in our yearly status and trend books” (2012b). Though their numbers may not have been clear, in the mid-1980s, desert bighorns once again roamed the Tobin Range, but they were not the only sheep in the neighborhood.

NEARBY DOMESTIC SHEEP

At the time of the Tobin outbreak, a domestic sheep flock existed on a ranch adjacent to the Tobin Range (Ward et al. 1997). According to Ward et al.:

“A portion of this flock grazed on the Tobin Range during the preceding summer. The length of time that the domestic sheep were on the various ranges was not known. It is estimated that domestic sheep trespassed on the Tobin Range for 2 to 4 [weeks] during the 1991 grazing season. Interaction of bighorn sheep and domestic sheep on the Tobin Range was probable but the duration of contact is unknown” (1997, 545).

Gregg Tanner provides more detail on the domestic sheep situation in the Tobin Range during the 1980s and early 1990s. However, before delving into that material, it is relevant to provide context on his background because he serves as a primary information source for much of the policy analysis later in this section.

Tanner retired from the NDOW in 2004 with the statewide position of Game Bureau Chief. He was NDOW’s Supervising Game Biologist for Region 1 in 1984 when managers released bighorns onto the Tobin Range. Tanner supervised all game management programs in Nevada’s nine northwest counties. He was the biologist in charge of overseeing the Tobin reintroduction. However, he was a not a primary field biologist for the project. He worked with Phil Benolkin (another NDOW biologist) who was actually on the ground (or in the air via helicopter) when important events unfolded (Tanner 2012a).

While performing wildlife surveys via helicopter, NDOW biologists often saw stray domestic sheep on the range. The NDOW flew more missions than other wildlife agencies—often for statewide mule deer surveys in fall and spring. This put biologists in a good position to spot stray domestic sheep that were left on the range by operators who were done grazing in particular areas. The NDOW biologists began to pay more attention to stray domestic sheep after their disease threat to bighorns became more prominent and well-recognized in the 1980s. As a result, NDOW learned that a lot more stray domestic sheep roamed the range than they originally thought. During one helicopter deer survey, Benolkin saw bighorns interacting with domestic sheep in the Tobin Range area (Tanner 2012a). Such interaction may have led to a disease outbreak’s untimely annihilation of the Tobin Range’s desert bighorns.

OUTBREAK SUMMARY

In 1991, a respiratory bacterial infection afflicted the Tobin Range’s bighorns (Arthur et al. 1999; Cummings and Stevenson 1995). Anecdotal evidence caused NDOW to conclude that the Tobin bighorn die-off was most likely caused by pneumonia from domestic sheep (Tanner 2012b). According to Cummings and Stevenson, Tobin bighorns “initiated declines in August 1991 [that] coincided with detection of trespass domestic sheep in bighorn habitat. In July 1994, it was concluded the Tobin population no longer existed” (1995, 79). Ward et al. noted that “only one bighorn was located on this range in January 1992 and none were detected on that range in subsequent surveys” (1997, 553).

In January 1992, as a part of a disease study examining Tobin sheep and those from other Nevada populations, agency researchers captured the last known (at the time) Tobin bighorn via helicopter net-gunning. Personnel also herded trespassing domestic sheep out of the Tobin Range. Biologists collected nose and throat swab samples from the bighorn and domestic sheep and checked them for the presence of pneumonia bacteria. Some pneumonia bacteria (e.g., Pasteurella trehalosi and Biotype 3 M. haemolytica) were found in samples from the Tobin bighorn and domestic sheep from the Tobin Range (Ward et al. 1997).

Regarding their overall study (which included non-Tobin bighorns), researchers concluded “that transmission could have occurred by nose-to-nose contact of the two sheep species and potentially by aerosols produced if animals coughed or sneezed during periods of intermingling” (Ward et al. 1997, 554). They add:

“Potential pathogenic strains of Pasteurella spp. in one population of bighorn sheep in which the organisms are indigenous may stimulate protective antibody production in that group of sheep but pose a threat to another population of bighorn sheep when first introduced. This potential should be considered when bighorn populations are being augmented by introducing sheep from other populations such as was done to augment the population on the Tobin Range in 1991” (1997, 555).

Despite the presence of bacteria, signs of illness were not observed in the captured Tobin bighorn. Researchers also did not report carcasses during their study. They stated: “Therefore, the causes of deaths [in the Tobin Range and the other study areas], believed associated with the loss of these populations, have not been identified” (Ward et al. 1997, 555).

This contradicts the response Cummings and Stevenson filled out in a 1999 questionnaire presented to biologists at the 2nd Annual North American Wild Sheep Conference. In response to the question “Have you had a disease die-off in the last 25 years?”, they responded by marking “Yes” and listing “Respiratory bacterial infection – Tobin Range, Pershing County” next to “Cause and herd name” (Arthur et al. 1999). Ward et al.’s population history for the Tobin bighorns (1997) only references one die-off, so the outbreak to which Cummings and Stevenson refer is most likely the same one that occurred in 1991. In a 2009-2010 big game status report, NDOW vaguely states: “For a multitude of reasons, bighorns failed to establish themselves in the Tobin Range” (2010, 59). Ward et al. emphasized that a disease link between wild and domestic sheep was inconclusive in their study because no samples were taken from sheep before mingling (1997). Retired NDOW biologist Jim Jeffress notes that the Tobin disease analysis was performed when wild-domestic sheep disease sampling and monitoring techniques were still in their infancy (2012b).

Despite the Tobin bighorns’ disease-related disappearance, wildlife managers reintroduced bighorns to the Tobin Range in 2003 with 23 animals from central Nevada’s Toquima Range (NDOW 2010; Google Earth 2012). In 2008, this population was augmented with 22 additional Toquima bighorns (NDOW 2010). During a September 2011 survey, 47 bighorns were counted in the Tobin Range (NDOW 2012). The second reintroduction seems to be a success. However, before biologists attempted their first reintroduction of desert bighorns to the Tobin Range, they were guided by a variety of policy documents.

POLICY DOCUMENTS

The BLM’s 1982 Sonoma-Gerlach Management Framework Plan (Sonoma-Gerlach MFP) covered the Tobin Range during the 1990s outbreak. However, that plan was drafted before a Tobin bighorn population was established in 1984. Nonetheless, the plan considers possible bighorn presence in the future. While desert bighorns ended up being established in the Tobin Range, the BLM plan only mentions California bighorns (BLM 1982).

In the plan, the BLM remarks that “California bighorn sheep are not present in the planning area, but fourteen . . . potential areas for reintroduction have been identified” (BLM 1982, Sec. 46, 79). The Sonoma-Gerlach MFP lists the Tobin Range as potential bighorn habitat and touches on wild-domestic sheep interaction policies (BLM 1982). For example, the BLM states: “Domestic/bighorn sheep conflicts may be a serious problem in some areas. Many of the mountain ranges in the resource area have been identified as potential bighorn sheep habitat. Elimination of domestic sheep use in an area used by bighorns would avoid potential disease and forage competition problems” (Sec. 44, 108).

In explaining its stance regarding prohibition of bighorn reintroduction to active domestic sheep grazing allotments, the BLM notes: “The decision as originally written caused much concern among the sheep permittees of the resource area. They felt that if bighorn sheep were reintroduced into the resource area that the domestic sheep operations would be eliminated. This was never the intention of the original decision” (BLM 1982, Sec. 46, 9).

Another policy document relevant to the Tobin Range bighorn die-off is the BLM’s 1989 Rangewide Plan for Managing Habitat of Desert Bighorn Sheep on Public Lands (BLM 1989). According to that plan: “In carrying out BLM’s responsibilities regarding reintroducing desert bighorn into historic habitats, BLM will be guided by established procedures as recommended by the Desert Bighorn Council [DBC] . . . and by newly accepted practices as they are developed” (BLM 1989, 19). The BLM adds: “For additional guidance on management of desert bighorn habitat, BLM will use established guidance as recommended by the Desert Bighorn Council . . . or subsequent updates” (BLM 1989, 19).

The latest DBC guidelines at the time of the Tobin Range epizootic were its 1990 recommendations in Guidelines for the Management of Domestic Sheep in the Vicinity of Desert Bighorn Habitat (DBC Technical Staff 1990). However, while considered, these guidelines did not become BLM advisory policy until 1992 (Brigham, Rominger, and Espinosa T. 2007). Additionally, while the DBC’s 1990 guidelines may have delayed or prevented disease, they were released in the year before the Tobin Range’s 1991 die-off, and with the slowness of bureaucracies, it is doubtful much could have been done to implement them fast enough to make a difference. Nonetheless, these guidelines existed at the time of the die-off, so they still got plugged into later analysis criteria question answers. Regarding the pre-1990 DBC guidelines and future updates, the BLM notes: “These guidelines will not be used to override management decisions already made through the land-use planning process” (BLM 1989, 19-20). While various guidelines may have smoothed tensions to some extent, the new coexistence of wild and domestic sheep in the Tobin Range sparked conflict and litigation.

LITIGATION

Before examining specific Tobin Range policies, it is helpful to provide background on influential litigation focused on bighorn-domestic sheep interaction in the area. This litigation foreshadowed future cases focused on protecting bighorns or retaining domestic sheep grazing rights. According to Tanner, the outcome of the Tobin litigation had a cultural and scientific impact on the bighorn-domestic sheep disease topic. The litigation encouraged research of the disease problem and brought up the issue of range rights vs. privileges (2012a).

In 1986, the Joe Saval Company requested a permit from the BLM that would allow it to graze 175 un-herded domestic sheep in the South Buffalo Allotment on the east side of the Tobin Range (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991). During the planning process that led to the 1982Sonoma-Gerlach MFP, at least one portion of this allotment was modified to allow only cattle grazing. The modification was part of an effort to prepare the Tobin Range for a future bighorn population (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991; Tanner 2012a).

In 1987, the BLM District Manager for the Battle Mountain District “approved the application of the Joe Saval Company (Saval) to graze 175 sheep within the Buffalo Valley Allotment, but excluded grazing in the vicinity of Buffalo Ranch and the east side of Mt. Tobin on the basis that such use in those areas was in potential conflict with bighorn sheep” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 202). These were areas in which Saval wished to run domestic sheep (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991). In 1988, the BLM Area Manager for the Shoshone-Eureka and Sonoma-Gerlach Resource Areas issued an environmental assessment that considered “the potential conflict between domestic and bighorn sheep in the western portion of the South Buffalo Allotment, in light of Saval’s request to convert its grazing preference in that area from cattle to sheep” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 203).

In an effort to allow sheep grazing, Saval suggested some possible forms of mitigation that would allow its domestic sheep to coexist with bighorns. The suggestions are listed below.

“(1) a health program including vaccination and disease control; (2) a 1-mile buffer zone; (3) sheep-proofing the western allotment boundary by fence construction; and (4) site management practices to provide higher quality water while reducing breeding areas for some insects and disease-causing organisms. Saval also offered to reimburse NDOW for bighorn deaths proven to be caused by the presence of their domestic sheep and to give up use in the Stillwater Range in return for use in the Tobins (Exh. R-11 at 3)” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 203).

The BLM Area Manager rejected Saval’s mitigation recommendations and decided not to allow conversion of the western portion of the South Buffalo Allotment from cattle to sheep (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991). The manager’s decision “was based on research indicating that declines and die-offs in bighorn sheep populations were aggravated by disease transmissions from domestic to bighorn sheep when the populations mingled” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 204).

In 1988, after an environmental assessment was issued, Administrative Law Judge Ramon A. Child presided over an evidentiary hearing focused on the Saval grazing issue. At the hearing, wildlife biologist George Tskuamato of NDOW and veterinarian David A. Jessup of the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) stressed the disease threat domestic sheep pose to bighorns. However, Marie Bulgin (of the University of Idaho) and Bobby Rand Hillman (of the Idaho Bureau of Animal Health) stressed that wild-domestic sheep interaction was not necessarily bad for bighorns’ health (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991).

Despite expert testimony from biologists, Judge Child ruled in favor of the Joe Saval Company: “In his [1989] decision, Judge Child concluded essentially that BLM erred in reserving a portion of the allotment for reintroduction of bighorn sheep, and that the District Manager’s limitation of Saval’s sheep grazing application was arbitrary and capricious” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 206). In Judge Child’s decision on the issue, he emphasized that bighorns could not be established in areas where domestic sheep grazed, unless all conflicts can be resolved. Judge Child focused on:“. . . the fact that Saval has private holdings within the western portion of the South Buffalo Allotment, Judge Child reasoned that 'all conflicts' could not be resolved 'without a condemnation proceeding to eliminate appellants’ and all private holdings on the potential bighorn sheep habitat on the Tobin Range where that habitat touches allotments wherein active sheep preferences exist’ (Decision at 8). Judge Child set aside the District Manager’s decision as being contrary to the [1982 Sonoma-Gerlach MFP], and directed BLM to grant Saval’s application without restriction” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 206).

With his ruling, Judge Child directed the BLM to allow Saval to run sheep on the Tobin Range, but the BLM and NDOW appealed the judge’s decision (which attempted to remove domestic sheep restrictions put in place to help bighorns). The language in the Sonoma-Gerlach MFP regarding necessity of conflict resolution for bighorn transplants involves active preference sheep allotments. According to the decision regarding the Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW: “The portion of the MFP relied on by Judge Child stated that ‘[b]ighorn sheep will not be reintroduced on active preference sheep allotments unless all conflicts can be resolved’” (1991, 207).

According to the BLM, “active preference” refers to “that portion of the total grazing preference for which grazing use may be authorized” (2005). All of Saval’s use of the South Buffalo Allotment since 1978 had been with cattle, which were the active livestock preference on the allotment. Saval’s “sheep use [had] shifted from active preference to exchange-of-use” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 207). The South Buffalo Allotment was no longer an active preference sheep allotment because Saval had exchanged sheep use for cattle use. Thus, with the allotment not being an active preference sheep allotment, conflict mitigation was a more important deciding factor than conflict resolution. Conflict mitigation could not be achieved, and the BLM acted in accordance with the Sonoma-Gerlach MFP with its 1987 decision. So, in a 1991 decision, the Interior Board of Land Appeals (IBLA) reversed Judge Child’s decision and upheld the BLM’s domestic sheep restrictions in the Tobin Range (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991).

The 1991 IBLA decision states that “a preponderance of documentary and oral evidence supports the wisdom of [wild-domestic sheep separation]” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 208). It goes on to remark:

“No significant challenges, in terms of contrary scientific findings, were put forward to impugn the conclusions of the Goodson paper and the Jessup articles. At the hearing, the thrust of the Saval evidence on conflict between the two species was to review and critique, not contradict, the evidence presented by BLM and NDOW. The record fully supports the action taken by BLM and Saval has failed to meet its burden of proving otherwise, or of showing that its grazing rights have been injured. Therefore, in the grazing application under appeal, BLM properly restricted the western third of the allotment in the interest of the potential reintroduction of bighorn sheep” (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991, 208-209).

Now that an overview has been presented on the Tobin Range’s 1991 desert bighorn disease outbreak and related factors, it is time to analyze some specific policies that could have prevented or worsened that outbreak. These policies are analyzed by looking at questions that compose nine policy analysis criteria.

POLICY ANALYSIS CRITERIA

1.) Were clearly defined buffer zones established to ensure separation of bighorns and domestic sheep?

Answer and Explanation

Clear buffer zones were not in place (Tanner 2012a). At the time of the establishment of the Tobin bighorn population in 1984, wildlife managers still poorly understood the biology of the wild-domestic sheep disease problem. The transmission mechanism was not yet clearly comprehended, and the role of nose-to-nose contact was not yet recognized. In the early years of transplants, biologists also did not know the extent of wild or domestic sheep movements very well. Additionally, in the early 1980s, NDOW biologists did not know just how many stray domestic sheep were left in the field after the grazing season was over (Tanner 2012a).

Policy

The DBC’s 1990 guidelines state: “No domestic sheep grazing should be authorized or allowed within buffer strips ≥13.5 km [8.4 mi] wide surrounding desert bighorn habitat, except where topographic features or other barriers prevent any interaction” (DBC Technical Staff 1990, 34). NDOW’s 1978 desert bighorn biological bulletin recommends that “grazing by domestic sheep should not be allowed in any areas occupied by desert bighorn sheep during any time of the year” (NDFG 1978, 73).

2.) Were special supervision rules in place for sheepherders?

Answer and Explanation

Supervision rules were not in place for the same reason buffers were not in place. Wildlife managers still had an incomplete understanding of the wild-domestic sheep disease issue (Tanner 2012a).

Policy

The DBC’s 1990 guidelines recommend that: “Domestic sheep that are trailed or grazed outside ≥13.5-km [8.4-mi] buffer, but in the vicinity of desert bighorn ranges, should be closely supervised by competent, capable, and informed herders” (DBC Technical Staff 1990, 34).

3.) Were domestic sheep trailing restrictions in place to ensure separation?

Answer and Explanation

Trailing restrictions were not in place because wildlife biologists still did not fully understand the bighorn-domestic sheep disease problem (Tanner 2012a). Also, according to Tanner, in Nevada, some domestic sheep grazing permittees did not and still do not want the BLM to know where and when they trail their sheep. Cultural factors explain this. Sheep grazers have had a tendency to resist being controlled by the federal government, and they have embraced the Sagebrush Rebellion mindset (Tanner 2012a).

Policy

The DBC’s 1990 guidelines recommend that: “Domestic sheep should be trucked rather than trailed, when trailing would bring sheep closer than ≥13.5 km [8.4 mi] to bighorn range. Trailing should never occur when domestic ewes are in estrus” (DBC Technical Staff 1990, 35).

4.) Were policies in place or was consideration taken regarding the concept of prohibiting bighorn reintroduction to the site if it hosted domestic sheep?

Answer and Implementation

Before desert bighorns were reintroduced to the Tobin Range, wildlife and land managers directly considered the presence of domestic sheep (BLM 1982; DBC Technical Staff 1990; Jeffress 2012a; Tanner 2012a). After planning, NDOW got clearance from the BLM to release bighorns into the Tobin Range. It got such clearance from the planning process that produced the 1982 Sonoma-Gerlach MFP. The NDOW made a special effort to “clear” transplant sites before reintroducing bighorns. This means it got BLM approval decisions and documents in place before reestablishing wild sheep populations (Tanner 2012a).

Policy

Prior to the 1984 reintroduction of bighorns to the Tobin Range, there was an internal NDOW policy not to release bighorns into areas with domestic sheep (Tanner 2012a). Also, according to the BLM’s 1982 Sonoma-Gerlach MFP, “bighorn sheep will not be reintroduced on active preference sheep allotments unless all conflicts can be resolved. The domestic sheep permit will remain transferable as a sheep permit. Established, permitted sheep trailing routes will be considered in the same sense as active preference sheep allotments” (BLM 1982, Sec. 46, 8). Additionally, the DBC’s 1990 guidelines state: “Bighorn sheep should not be reintroduced into areas where domestic sheep have grazed during the previous 4 years” (DBC Technical Staff 1990, 35).

5.) Before the disease outbreak, was any effort made to buy out nearby domestic sheep grazing allotments or convert them to cattle?

Answer and Implementation

Grazing allotment alteration occurred in the Tobin Range before the 1984 desert bighorn reintroduction occurred (Tanner 2012a). During the planning process that led to the 1982 Sonoma-Gerlach MFP, a portion of an allotment in the Tobin Range area that could be used for cattle or sheep was basically locked into use by cattle (Tanner 2012a; Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991). It could not be modified to allow sheep grazing again. When bighorns were transplanted to the Tobin Range, only cattle grazed on the allotment (Tanner 2012a).

Policy

Range Policy from the BLM’s 1982 Sonoma-Gerlach MFP states: “Allow for conversion from cattle to sheep on all allotments within the resource area except where conflicts with bighorn sheep would occur” (BLM 1982, Sec. 44, 110). The plan adds: “Allow for conversion from sheep to cattle on a case-by-case basis. Conversion ratio and authorization will depend upon the suitability of the rangeland involved and will be made only where cattle can be adequately controlled and managed” (BLM 1982, Sec. 44, 110).

6.) Were other forms of negotiation and/or education attempted with local stakeholders regarding the issue of bighorn-domestic sheep disease transmission?

Answer and Implementation

Various forms of negotiation occurred during litigation that ran through the 1980s and 1990s (Tanner 2012a; Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991). See the “Litigation” commentary that starts earlier in this section for more information. In Nevada, certified letters were also sent to all livestock permittees (including non-sheep operators) in areas that could potentially be affected by particular bighorn transplant efforts (Tanner 2012b).

Policy

Due to accelerated bighorn reintroduction efforts in Nevada, the livestock industry in the state viewed NDOW’s wild sheep transplant program as a significant threat. So, in the 1980s, the Nevada Wildlife Commission passed a policy requiring NDOW to formally notify (through certified mail) livestock operators of bighorn reintroduction plans that would take place in their grazing areas (Tanner 2012a). Sending out letters was a political action to dispel some locals’ perceptions that NDOW’s bighorn program was operated with secrecy (Tanner 2012b).

7.) If wandering bighorns got too close to domestic sheep, were they ever removed from the wild in or near this location?

Answer and Explanation

Bighorns that got near domestic sheep were not removed from the wild in the Tobin Range. After domestic sheep contact had been detected, the Tobin bighorns did not survive long enough for fatal removal to cause any benefit (Tanner 2012b).

Policy

Lethal bighorn removal was not really considered an option for NDOW until fairly recently (within the last five to six years) (Dobel 2012a).

8.) Did coordination and/or tension exist between different levels (federal, state, local) of government management agencies regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction?

Answer and Nature

The NDOW and the BLM heavily coordinated communication and activities regarding the issue of domestic sheep disease possibly being a problem for bighorns in the Tobin Range. As discussed earlier, NDOW worked directly with the BLM to clear the Tobin Range in preparation for establishing bighorns there (Tanner 2012a).

There was good cooperation between NDOW and the BLM regarding the establishment and management of the Tobin bighorn population. The BLM and NDOW encountered opposition from the State Department of Agriculture at a statewide level. However, this happened after the Tobin die-off and was not an issue in the Tobin Range. The Tobin transplant happened too early for the disease issue to be prominent enough to cause major opposition from the State Department of Agriculture (Tanner 2012b).

In the 1990s, tension existed at the state level. In the answers to a questionnaire presented to biologists at the 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference in 1999, Cummings and Stevenson elaborate on state-federal relationship challenges regarding desert bighorn management in Nevada. Many of the general topics they address could apply to bighorn-domestic sheep interaction policy:

“Federal land management agencies tend to have many conflicting objectives and plans. The schizophrenic nature of multiple use agencies is often the root of unnecessary delays relative to obtaining required clearances and permits for wild sheep projects.

Wildlife programs and concerns within the federal land management agencies ordinarily do not extend much beyond feral horses and burros, and species which are federally listed as threatened or endangered. Consequently, the welfare of wild sheep populations and management of wild sheep habitat often receives little consideration. Moreover, management actions within the scope of feral horses and burros, and threatened and endangered species usually have profound impacts on bighorn sheep habitat, distribution, and movements.

The high turn-over rate of personnel from Washington to the field ensures many federal employees lack background knowledge on critical issues, and lack intimate knowledge of resources under their responsibility. In short, brief tenure breeds unfamiliarity on many levels, and ultimately serves to delay issuance of essential clearances and permits for desert bighorn sheep projects and activities” (Arthur et al. 1999, 451-452).

9.) Did you encounter funding difficulties regarding bighorn-domestic sheep interaction management?

Funding difficulties pertaining to the management of bighorn-domestic sheep interaction were not an issue in the Tobin Range (Tanner 2012b).

POLICY EFFICACY SUMMARY

Regarding wild-domestic sheep interaction in the Tobin Range before its bighorn disease outbreak, some policies were missing, some logical policies were in place, and implementation was often ineffective. Clear buffers, special supervision rules for sheepherders, and trailing restrictions were not in place (Tanner 2012a). The absence of these policies contributed to the Tobin Range’s bighorn die-off. Nonetheless, domestic sheep presence was considered before bighorn reintroduction, grazing allotment alteration occurred, and negotiation and education took place (BLM 1982; Tanner 2012a). The implementation of these policies probably helped delay the die-off of bighorns in the Tobin Range, which indicates some policy efficacy. However, though part of an allotment was restricted (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991), domestic sheep still existed in the Tobin Range (Ward et al. 1997) and were not sufficiently managed to prevent disease. Also, negotiation proved largely ineffective because a local sheep producer was hostile enough to initiate litigation (Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991) and did not manage domestic sheep in a manner that prevented interaction.

In the Tobin Range, bighorns near domestic sheep were also not removed (Tanner 2012b). Not removing bighorns seen interacting with domestic sheep could have been a mistake, though one wonders if this would have done much good without concurrent strengthening of other policies. For the Tobin Range, agency coordination also took place, and interagency tension and funding were not major problems (Tanner 2012a, b). Despite what seemed to be sincere, logical coordination between agencies (e.g., the BLM and NDOW teamed up to defend themselves against sheep rancher litigation in Joe Saval Co. v. BLM and NDOW 1991), this coordination could have been more effective because it still did not improve policies enough to prevent disease.

REFERENCES

Arthur, Steven M., Ian Hatter, Alasdair Veitch, John Nagy, Jean Carey, Jon T. Jorgenson, Raymond Lee, John Ellenberger, John Beecham, John J. McCarthy, Gary Schlichtemeier, Larry T. Gilbertson, Bill Dunn, Don Whittaker, Ted A. Benzon, Jim Karpowitz, George Tsukamato, Kevin Hurley, Steven G. Torres, Craig Mortimore, Mike Oehler, Patrick Cummings, Craig Stevenson, Eric Rominger, and Doug Humphreys. 1999. Appendix A: Wild sheep status questionnaires. In proceedings of 2nd North American Wild Sheep Conference, Reno, NV. April 6-9.

Brigham, William R., Eric M. Rominger, and Alejandro Espinosa T. 2007. Desert bighorn sheep management: Reflecting on the past and hoping for the future. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 49th Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV. April 3-6.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1982. Sonoma-Gerlach Management Framework Plan. Reno, NV. http://www. blm.gov/nv/st/en/fo/wfo/blm_information/rmp/documents.html (accessed May 29, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1989. Rangewide Plan For Managing Habitat of Desert Bighorn Sheep. Washington, D.C. https://books.google.com/books?id=Y6zwAAAAMAAJ&pg

=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=Rangewide+Plan+For+Managing+Habitat+of+Desert+Bighorn+Sheep

&source=bl&ots=7FeNzbMqXf&sig=JyEjA_pI7fC4GAJtGxmuC5bDmzM&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wX

7VI_HLomrogTksIDoBA&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Rangewide%20Plan%20For%

20Managing%20Habitat%20of%20Desert%20Bighorn%20Sheep&f=false (accessed May 20,

2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 1995. Mountain Sheep Ecosystem Management Strategy in the 11 Western States and Alaska. N.p. ftp://ftp.blm.gov/pub/blmlibrary/BLM publications/StrategicPlans/Wildlife/ MountainSheepEcosystem.pdf (accessed May 11, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2005. Vernal Field Office: Draft Resource Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, January 2005. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/ medialib/blm/ut/vernal_fo/planning/draft_eis/glossary.Par.42735.File.dat/Glossary.pdf (accessed March 23, 2013).

Bureau of Land Management (BLM). 2012. Tobin Range Wilderness Study Area. N.p. http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/nv/field_offices/winnemucca_field_office/

wsas.Par.94117.File.dat/Tobin%20Range.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Cummings, Patrick J., and Craig Stevenson. 1995. Status of desert bighorn sheep in Nevada – 1994. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 39th Annual Meeting, Alpine, TX. April 5-7.

Desert Bighorn Council Technical Staff. 1990. Guidelines for the management of domestic sheep in the vicinity of desert bighorn habitat. In transactions of Desert Bighorn Council’s 34th Annual Meeting, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. April 4-6.

Jeffress, Jim. 2012a. Idaho Wild Sheep Foundation Chapter Board of Directors Member/ Retired Nevada Department of Wildlife Biologist (Western Region). Interview by author. Conducted by phone. June 12.

Jeffress, Jim. 2012b. Idaho Wild Sheep Foundation Chapter Board of Directors Member/ Retired Nevada Department of Wildlife Biologist (Western Region). Interview by author. Conducted by phone. July 26.

Joe Saval Co. v. Bureau of Land Management and State of Nevada, Department of Wildlife, Intervenor. 119 IBLA 202 (1991). http://www.oha.doi.gov/IBLA/Ibla decisions/119IBLA/ 119IBLA202%20JOE%20SAVAL%20CO.%20V.%20BLM,%20NEVADA%20%28APPELLANTS% 29%205-7-1991.pdf (accessed November 5, 2012).

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). 2002. Plant Fact Sheet: Big Sagebrush. N.p. http://plants.usda.gov/factsheet/pdf/fs_artr2.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012).

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). 2012. Plants Profile: Artemisia L., sagebrush. http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile? symbol=ARTEM (accessed May 14, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Fish and Game (NDFG). 1978. The Desert bighorn sheep of Nevada. By Robert P. McQuivey. Reno, NV. [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2010. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2009-2010 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/10_bg_status.pdf (accessed December 24, 2011). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2012a. Mule Deer Hunter Information Sheet, See unit descriptions Unit 043, Unit 044, Unit 045, Unit 046. N.p. http://www.ndow.org/hunt/ resources/infosheets/deer/west/043_044_045_046deer.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012). [govt. doc.]

Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). 2012b. Nevada Department of Wildlife: 2011-2012 Big Game Status. Reno, NV. http://www.ndow.org/about/pubs/reports/2012_Big%20

Game%20Status%20Book.pdf (accessed June 9, 2012).

Tanner, Gregg. 2012a. Retired Game Bureau Chief (Statewide), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. October 31.

Tanner, Gregg. 2012b. Retired Game Bureau Chief (Statewide), Nevada Department of Wildlife. Interview by author. Conducted by phone. November 5.

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). 2012. Nevada Bighorn Sheep Occupied Habitat and Domestic Sheep Grazing Allotments. http://www.fs.fed.us/biology/resources/pubs/wildlife/sheep-maps/BighornSheep_NV_26x34_v10.pdf (accessed May 14, 2012).

Ward, A.C.S., D.L. Hunter, M.D. Jaworski, P.J. Benolkin, M.P. Dobel, J.B. Jeffress, and G.A. Tanner. 1997. Pasteurella spp. in sympatric bighorn and domestic sheep. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 33, no. 3 (July): 544-557.